This Conflicts of Interest Online post is from Alex Knight, designer of Land and Freedom: The Spanish Revolution and Civil War. In this piece, Knight interviews seven designers about their work on board games focusing on struggles for social justice, and how they see different issues affecting the hobby. (Also see our previous designer roundtable piece with Volko Ruhnke talking to seven different designers on challenging issues in historical board games.)

Alex Knight.

Introduction

Over the last few years, board games focused on struggles for social justice, whether historical, current day, or fictional, have been published in growing numbers. To investigate this phenomenon, I interviewed seven designers on the cutting edge of this trend to discover the sources of this board game revolution, the obstacles that remain, and what it means for the hobby going forward.

Designers:

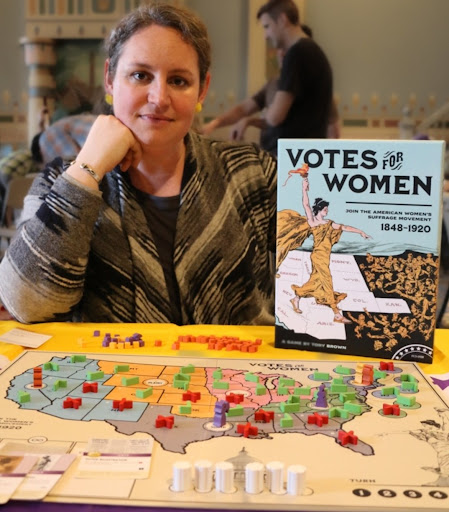

– Tory Brown – Votes for Women (2022)

– Jason Perez – cultural consultant on Puerto Rico 1897 (2022)

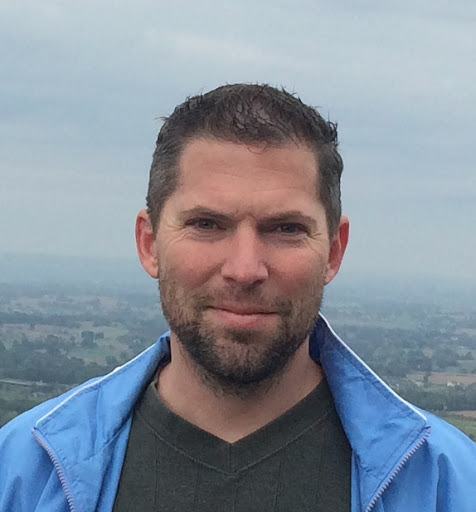

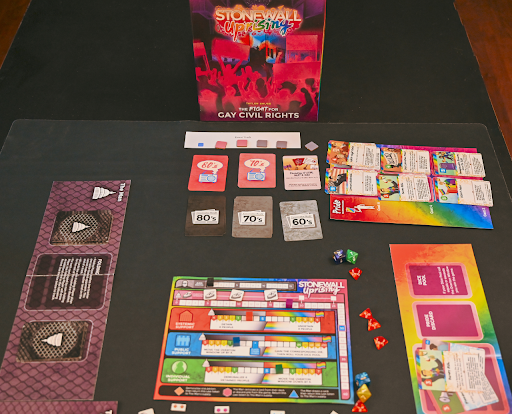

– Taylor Shuss – Stonewall Uprising: The Fight for Gay Civil Rights (2022)

– Fred Serval – (right, with developer Joe Dewhurst) – Red Flag Over Paris: The Rise and Fall of the Paris Commune (2021)

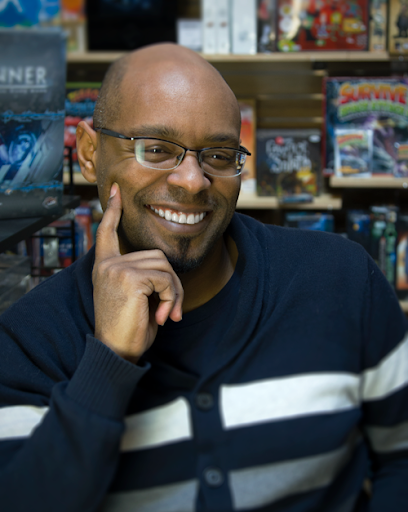

– Damon Stone – Free At Last (2022)

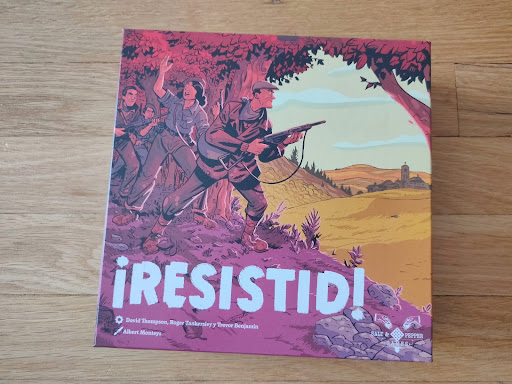

– David Thompson – Resist! (2022)

– Brian Van Slyke – Strike!: The Game of Worker Rebellion (2020), from TESA Collective

Questions and Answers:

Q: I’ve been encouraged that it seems there are more board games with social struggle or anti-oppressive themes in the past few years. Why do you think so many games covering these topics are coming out now?

Fred (Red Flag Over Paris): First of all, I think the political dimension of gaming already existed in the 19th and early 20th century, maybe even earlier. It’s just that it was occulted by the emergence of boardgaming as an industry in the 60s. But I agree that something significant has been happening in the last few years, or maybe the last couple of decades.

That’s due to a few things: new types of players and designers are coming into boardgaming, attracted by specific games like Pax and COIN or even earlier initiatives like the games by Brian Train. Those demonstrated that gaming is a relevant tool to talk about social movements in an interesting way. And a few publishers are now open to this because boardgaming is experiencing a golden age and there is space to explore new territories.

Finally, people born in the 80s and 90s, who are most of the new public in boardgames, are from a generation notably more left leaning, and the older they get, the more radical they become (contrary to previous generations that became more conservative over time). So we should expect even more of these types of games in the future.

Jason (Puerto Rico 1897): We’ve always had games against the grain. But in this particular moment they’re busting through a little bit more.

Wingspan is an underrated watershed moment, with Elizabeth Hargrave being who she is, and the game made by women up and down—designers, playtesters, artists. It’s a premium package with soup-to-nuts production values and an excellent game that has sold way more copies than the publisher expected.

Spirit Island was another one, flipping colonialism on its head. Those two games have expanded who can make hugely successful games and what those games can be about.

Tory (Votes for Women): It does feel like there are a lot of players who are hungry for these titles, who see it as valuable to explore this area of our history, and whose values align with the experience of fighting for rights and against oppression. If there are a billion titles I could buy, and that I’m going to post about on the internet, then the title I end up with should align with my values and the image I project to my community.

So a game like Spirit Island helps me communicate to my world that I understand the problem with and reject colonialist themes and instead choose to buy or post about a game that does the opposite. People choose board games as fashion as much as they do for function.

I have a vague sense that for every one misogynist who doesn’t want to play my game, there are 10 or maybe even 100 people who want to play it to prove they aren’t misogynistic or just want to play something different. And I’m glad for that.

Damon (Free At Last): With crowdfunding, designers who haven’t been able to break into the industry through traditional means have the ability to see their visions come to fruition and find an audience of gamers open to new and under-explored topics.

David (Resist!): I think it’s just a general reflection of society. A desire to embrace the importance of history and culture with our creative efforts. And what was traditionally viewed as the “wargame” hobby is now being broadened into the historical game hobby.

The lower barrier to entry for publishers is allowing smaller publishers to support a much wider variety of topics. Blue Panther enables themselves and other publishers like Hollandspiele to explore much more niche topics. But even something as niche as Resist! has a chance to have decent reach to a wider part of the hobby.

Taylor (Stonewall Uprising): People are thinking about games as art, about how games can address serious topics. There’s growing interest in these topics, games having conversations about people.

The board game market is oversaturated, so publishers are looking for markets and subgenres to fill to differentiate themselves. They want to expand and get out in front of things.

These are independent publishers for the most part. Larger companies aren’t in the business of being controversial. They’re focused on making family games.

Stonewall Uprising: The Fight for Gay Civil Rights (2022)

Brian (Strike!): We [TESA Collective] released our first game in 2011. At that time, there weren’t many social justice-themed games coming out. There are far more now, and they’re more explicitly about changing the world. It’s happening for a few reasons:

1) Games are becoming a more popular medium, and it’s becoming less niche and more normal.

2) Folks with progressive views have more tools now, like crowdfunding, online communities for playtesting, and social media to network and get the word out.

3) People adding their voices by making games they’re passionate about encourages other people to do the same, and it seems to have a snowballing effect.

Q: What about your experience – do you think you could have made the same game 10 or 20 years ago? How have movements like Occupy or Black Lives Matter shifted the board game industry?

Damon (Free At Last): There were some hard conversations after Black Lives Matter regarding the need for a public statement. And I think a few companies might have decided to make some attempts at low-hanging fruit. But there hasn’t been a sea change in employment practices, or who gets to be in the room where the decisions are made.

I see projects done by freelancers and changing problematic language for older games and a shift on that in newer games, but I don’t see a change in the demographics of those being hired. I don’t see more women or BIPOC or LGTBTQ people in positions of management or at the executive level.

I see more companies hiring cultural consultants and sensitivity readers but I don’t see those people given the role of editor, meaning they have no power to enact change or direct projects. They can just make a note and hope that someone decides to actually listen.

Jason: Black Lives Matter was a turning point. The groundswell was huge, and it both inspired designers as well as put pressure on publishers to listen. My first video about Puerto Rico 1897 was in 2021, after the George Floyd protests. And that movement convinced the publisher that a change needed to be made [retheming the game to make it about Puerto Rican farmers rather than a game about colonialism].

Brian: TESA Collective is a worker-owned cooperative. Our first game came out around the time of Occupy Wall Street, which changed online discourse and emboldened radical, progressive voices that made a more welcoming reception for our games.

Strike!, compared to our first games, also benefited from games in the last decade becoming more mature mechanically, as well as artistically. But we want to continue to make games that are as accessible as possible to reach people who aren’t necessarily gamers.

Strike!: The Game of Worker Rebellion (2020)

David: Resist! would have never been published 15 or 20 years ago, honestly. Only crowdfunding and the ability of small publishers to establish themselves really made it a reality. But even if it could have been published, I think it would have failed because of the expectations of players at the time. Wargamers back then would have never gone for the idea of an abstract card game like Resist! And hobby gamers would have been put off by the setting/theme [of anti-Franco maquis in Spain].

Fred: I’ve only started engaging with the hobby less than a decade ago, so take my opinion with a grain of salt. But 15/20 years ago I don’t think Red Flag Over Paris would have been published by a big publisher like GMT. Maybe I could have had a simple thematic card game published in France, but not a light historical board game like this.

Tory: I don’t know enough about the community 10 or 20 years ago to say what receptivity to Votes for Women might have been like then. But I was optimistic a struggle-for-justice game would be well received, and I don’t think my publisher would have taken the risk if he didn’t agree. Besides Amabel Holland’s The Vote, there isn’t another title like this. Clearly, woman suffrage is a pretty low intensity struggle at this point, it is very palatable because of the larger threats to American democracy. The racial justice aspect of the game is also integral to the gameplay and my intent as a designer. As is my call for players to find movements to join to be a part of the current struggle.

Taylor: I was expecting more obstacles to Stonewall Uprising. I did a big round of pitching, and then two companies were talking to me. You can never be sure why a company’s saying no to your game. It could be because they didn’t like your email, or it doesn’t fit their brand.

Q: How much resistance within the board game world have you experienced, either because of the themes of your games, or because of your race, gender, or sexuality? How do you handle online criticism, whether it’s in good faith or not?

Damon (Free At Last): I can’t explicitly state that there were any racial obstacles for me. But I’m pretty lucky. I developed a friendship with a designer who worked for a major company and they asked me to playtest one of their collectible card games. I did that for a few years, and eventually I was on their short list of people they wanted to turn the game over to.

It took me years of doing unpaid labor and being lucky enough to have a job that let me travel a bit. Most BIPOC couldn’t have managed those things.

But even in that company I had to push for greater representation at times in the characters being depicted and the art. And at least once I flat out said that if a piece of art for a character was final, to shelve the character and it would never see print while I was the designer. Because my friends, my family, my parents were going to eventually see that art and ask me what the hell was wrong with me.

And then there were bits and pieces where you get passed up to take the lead on the design of a new game and the reasoning given made no sense. It’s tied to entirely unrelated skills or abilities or just reeks of favoritism. And you are left wondering if the fully capable, but more junior, white person who got the opportunity was chosen for something you couldn’t ever achieve.

Even with a VP and the team’s senior designer having faith, your game being one of the largest profit creators, you still don’t get the same opportunities. But that is the problem when you are the only Black person who works for the studio, and one of four people of color, you just never know.

Taylor (Stonewall Uprising): What’s interesting about my game is that all the homophobes know they can’t be vocal in response to my game. Homophobes know this game’s not for them, they scoff and walk away. There’s a rating on BGG that’s a 1 that just says “THUMBS DOWN.” You have to ignore the haters. I get what I call 90%ers – someone who agrees with me 90%; they agree that systemic oppression is real, gay people have rights, etc., but they don’t like some aspect of how I’ve approached the topic. People who like queer issues and queer rights are more curious, but they still critique what they don’t see.

Tory (Votes for Women): I have been very fortunate to not experience any outright hostility or resistance. I’ve got a few negative reviews on BGG, but every game is going to have parts about it people don’t like. One harsh negative review came before the game’s release but, as in a lot of gender discrimination cases, it’s hard to know or prove exactly why someone is being a garbage human being and whether bias motivates that action.

If there are spaces in the board game world where people are openly expressing their disdain for justice-themed games, I’m thankfully not hanging out there. My instinct is to challenge the internal logic of bias, I want to debate and suss out that whatever else is going on. But fortunately BGG doesn’t have a reply option on ratings.

As I take a breath and then another, I let go. I read the positive reviews, and I think about the people I’ve talked to who tell me the game is fun to play and informative.

First, you should expect and prepare for criticism. Assume it’s coming and depersonalize as much as possible. It’s not me that’s being criticized but this piece of work, this person doesn’t know me. Second, separate the “If I had designed the game I would have done X” comment from the “This sucks” comment.

Third, there’s reframing criticism as a kind of validation of the work. People don’t seem to take much pleasure in dumping on games no one has heard of. And I think you generally have to have thick skin to be a woman on the internet today, whether you design games or not.

Brian (Strike!): We got a lot of blowback from conservatives and fascists to our game Space Cats Fight Fascism when it launched in 2018. We tried to spin that as “buy this game to piss off fascists,” but that didn’t really work. It was a valuable lesson.

If you want someone to buy your game, it works better if they genuinely want to play it. We got a lot more response from just focusing on what’s great about the game–exploring liberation in a fun and funny way. It taught us that passion-engagement gets you fans and a community, which is more effective than anger-engagement.

And I have much less interest these days engaging with haters and trolls. It’s much more fun and exciting interacting with people who like your ideas. I don’t care if that’s preaching to the choir. Sometimes the choir needs a tune-up.

Fred (Red Flag Over Paris): I didn’t experience push back from the publisher at all, but I have on a few occasions from the community. Whether I respond really depends on the criticism and my current state of mind.

I’ve had some mental health issues over the last couple of years that sometimes prevented me from really engaging with criticism unfortunately. But normally I try to assess a few things before answering:

1 – Is the criticism made in good faith and is there actual room for debate?

2 – Is it possible that there is a misunderstanding at the core of the disagreement?

3 – Is there value in engaging? This one is tricky, but it’s either “can I change that person’s mind?” or “could it be useful to someone reading our exchange?”

Once I’ve evaluated those three things, I decide the course of action I want to take. But sometimes I don’t have the strength. And sometimes I can be a bit immature and just make fun of people, which doesn’t always help. But for defending the Red Flag Over Paris design, I didn’t step away from any fights.

Red Flag Over Paris: The Rise & Fall of the Paris Commune (2021)

Jason (Puerto Rico 1897): I’ve experienced a lot of resistance within the hobby. The center of the hobby remains middle- to upper-class straight white, and male. We’re challenging that default perspective which tends to make the colonizer the hero. Tell us stories from different perspectives, new angles.

Publishers are reading the market, but they’re on a time delay. They’re risk-averse and they go to familiar themes, Cthulhu, tomb raiding, etc., because it works. They don’t care, they just want to make money. Convincing them of a moral argument to change has been very difficult, so we have to make a sales argument.

Responding to negative or hateful comments, I’m a trained conversational specialist—I do crisis intervention and family therapy. I differentiate between commenters who are coming from a place of meanness—I don’t engage that; that’s aggression.

But there are other people expressing aggrievement; they’re triggered, they’re afraid. I try to convince those people they have nothing to be afraid of, we’re not trying to sweep them out of the hobby.

I’ve had some great experiences with that, but it’s really for the person reading the comment thread. I’ve gotten people saying “Wow, I saw what you did.” But I’ve developed a baseline of “let me answer that person’s fear,” and if I haven’t convinced them, that’s when I close the laptop and take a walk.

David (Resist!): I got quite a bit of backlash about supporting communism, blah, blah, blah. I just ignored it. I’ve had similar things happen to other games, especially Undaunted. The racists and the sexists have come out in full force against those games because of the representation in them.

I set folks straight about both the women in the Red Army during WW2 and the diversity of pilots in the RAF. I’ve had MANY conversations about integrated platoons in WW2. So I always correct factual things. But I don’t engage with any pure hatred review bombs.

In general, our hobby (the historical gaming hobby especially and the wargaming side too, to a lesser extent) is getting better. But there are still a lot of right-wing, super loud folks. But the great news is that we’re part of a new generation of creators and media folks who truly want more diversity, more interesting topics, etc. in our games. Things are definitely moving in the right direction.

Q: I’d like to encourage more of these games that highlight struggles for justice and equality, and to amplify designers from underrepresented backgrounds in the gaming industry. What kind of support would you like to see for new voices and new perspectives entering the hobby?

Brian (Strike!): If you see a game about an underrepresented community or by a designer from that community, support that game–share it on social media, buy it, and have each other’s backs. It’s important not to have feelings of competition or jealousy.

We need to uplift voices outside the mainstream, as well as making space for new voices. Give each other passion and engagement. There are segments of the board gaming community that are super welcoming, excited to include new voices and new topics. But that’s not universal.

Women and non-binary designers are barely featured or properly represented within the industry, despite possibly half of board game players being women or non-binary. There’s structural reasons for male designers having advantages in terms of getting published, which are reflective of society in terms of men having more free time, etc.

Queer folks, BIPOC, and women are always creating things to express their perspectives. But there’s a bottleneck in terms of creations that get published and promoted.

If there’s resistance to the topics or themes that these designers make due to being “too political”, why is that not applied to a game like Watergate for example, which is obviously about a very political event? Or even games about conquest or colonialism, which haven’t been considered “political” because they’re considered the norm. Who’s making the decision on what games to publish or promote, and what do those decisions say about their views?

Tory: Some of it is being in community with each other, striking up these kinds of conversations, amplifying and supporting the work wherever we are. I often bring up Stonewall Uprising unprompted in podcasts as a movement game that takes a very different approach to depicting opposition/The Man than I did in Votes for Women.

Looking for panels and speaking opportunities to bring each other along is also on my To Do list.

There’s something fundamental about doing the work well, it’s a notion that Black women in the suffrage movement referred to as “Lifting as we climb” that our success helps create other’s success.Creating well-selling, popular titles about the struggle against oppression proves to publishers, retailers, and content creators that players are hungry for and willing to buy these titles.

Votes for Women (2022)

Taylor (Stonewall Uprising): I want to see broader thematic expression. We see so many games about milquetoast themes that are easy to show off & playtest because they are safe.

Accepting that games can be about larger systemic problems and ways we’ve come to accept them culturally/structurally, and likewise about ways we can overcome these problems, is a huge shift that will remain niche for some time. Even with this wave of socially-aware games hitting the market.

Getting designers to embrace that games can hit these themes and ideas hopefully emboldens designers unsure if they can talk about issues important to them. And it allows for that exploration in relatively safe environments.

Of course, as games evolve and hit wider audiences because of getting published, there will always be naysayers. But new voices and ideas are worth it, so tearing down those barriers on the designer side is the least we can do. Publishers are a tougher nut to crack, but if there is a proven market, it’ll be an option.

Damon (Free At Last): I think networking, putting forward names of other designers to publishers, and sharing crowdsourced games to our social media followers is about the most designers can do. The onus is on the publishers. They are the ones with all the power in the industry.

Jason: On the designer end, we can do a lot to get ourselves together, support each other and help each other. If we want to really step it up and gain influence, we need to go after the bigger publishers. Try to design games that will fit with those bigger imprints, and make those connections.

I’m hoping that Puerto Rico 1897 does well, opening the door for more alternative stories to get that bigger platform. If something comes out that’s questionable, say something! And figure out a way to say it beyond the Twitter bubble – make videos, games, interviews.

David (Resist!): I’m blessed in many ways, because my games straddle both the historical/wargame world and the broader hobby market. I try to be vocal with my support for any designer/publisher whose work I genuinely support. Tory is easy to support, as is Taylor, because they are good people, supporting good causes, and their games are also of high quality.

I don’t just support everyone all the time. But I try to be open and vocal of my support whenever possible, especially on places like Twitter, Facebook, and BGG, where I have at least some reach. I also make sure to talk about the work they’re doing to advance our hobby during interviews.

And of course there are more well-organized opportunities such as the Zenobia Award, which I’m a mentor for, and the SDHistCon crew, which I’m an advisor for, too. I just try to help where and when I can, and hope that my little piece effects some positive change, even if it’s a small amount.

Spanish version of Resist! (2022)

Fred (Red Flag Over Paris): This recent surge in board games focusing on social justice issues is for sure a positive trend. But it’s crucial to ensure that this momentum translates into a lasting change and a more inclusive hobby. Here are some thoughts on how to support new voices and perspectives:

- Mentorship and Collaboration: Encourage established designers to mentor newcomers, fostering a supportive environment where knowledge is shared freely. Collaboration can lead to innovative and impactful games.

- Inclusive Events: Promote gaming events, both online and offline, and of different sizes, that celebrate diversity in game design. These events can provide a platform for underrepresented voices to showcase their work.

- Educational Initiatives: Support programs and initiatives aimed at introducing people from diverse backgrounds to historical games and game design. By making resources and guidance available, we can also empower aspiring designers to bring their unique perspectives into the industry.

- Diverse Themes: Encourage the exploration of a wide range of themes in historical gaming. By diversifying the subjects of games, we can engage players with narratives that reflect a broader spectrum of human experiences.

- Encourage Uniqueness: Embrace the notion that diversity leads to a richer tapestry of games. Encourage designers to create games that offer new and thought-provoking experiences.

In an ideal future, I envision a board gaming industry that mirrors the indie video game scene, where smaller companies find their niches and produce unique, mature, and culturally diverse games. By nurturing talent from diverse backgrounds, we can spark meaningful dialogues among designers, ultimately leading to a more vibrant and inclusive hobby.

I guess that the natural next step would be to think about how the games are actually made, from design to production, to really make significant changes. But that’s probably another discussion.

Alex Knight is a board game designer making games to inspire people to make positive social change. His first published game is Land and Freedom: The Spanish Revolution and Civil War from Blue Panther. Other prototype designs cover the Russian Civil War and John Brown’s anti-slavery quest.

In addition to game design, Alex is a teacher of English as a Second Language and a semi-avid cyclist. He lives in Philadelphia. You can follow his design process via Twitter, Bluesky, or Instagram.