This post is from Matthew Kirschenbaum, a gamer based in the Washington DC area, where he teaches at the nearby University of Maryland. With Pat Harrigan, he is the co-editor of the book Zones of Control: Perspectives on Wargaming from the MIT Press (2016).He is a frequent contributor to hobby forums and publications.

From counters to figures

Warlord Games or GMT? Rick Priestley or Richard Berg (or Borg)? Bolt Action or Advanced Squad Leader? TMP or CSW? Wargames Illustrated or Strategy and Tactics? Historicon or the WBCs?

Of course some readers will have no trouble recognizing both halves of each of these pairs. But for many, the wargaming table is divided by an unbridgeable chasm of lead vs. cardboard.

Matthew Kirschenbaum.

On the one side are the miniatures gamers, with their brushes and paint pots, their army lists and Osprey uniform books. On the other are the hex and counter grognards, with their tweezers, laminate clippers, and enormous sheets of plexiglass for flattening maps.

To step from one side of this divide to the other is to discover a mirror world, a second wargaming hobby that has been there all along but perhaps studiously ignored for reasons (in individually varying quantities) of time, taste, snobbery, and fiscal probity.

I have been a hex and counter wargamer for much of my life. I swore I would never get into miniatures. They intimidated me. Even setting aside the expense, there was the whole artisanal dimension of painting and terrain making, things I not only convinced myself I would never enjoy but also that I could never possibly be any good at.

I didn’t know the business end of an airbrush or a hot glue gun and I had no desire to learn. I balked at cutting out overlays for ASL; how was I possibly going to get a squadron of Uhlans in their bare metal state of nature ready for the tabletop?

Then the pandemic hit. I found I suddenly had a lot of extra time on my hands and also the need of some urgent retail therapy. Miniatures promised something new and shiny when every day felt much like the numbing last.

So I bought 28mm French and Indian War figures for skirmish gaming and some paints. Also a good hobby knife, brushes, and glue. I watched a lot of YouTube videos.

I learned how to clear away flash and mould lines. I learned how to prime. I learned about bases and layers, highlights and shades, wet blending and dry brushing, contrast paints and speed paints; at times it felt like a whole new language: Zenithal!

While I’m fortunate to live in an area with other figure gamers, miniatures are often underrepresented on this side of the pond. I’m hoping this short piece can help demystify what’s on the other side of the mirror.

But this is not intended as a guide to ”getting into” miniatures, still less as an actual primer on painting or any other particulars. Rather, I want to write about some things I hadn’t understood and had not appreciated or anticipated about figures and the kind of wargaming that goes along with them.

Not only is miniatures gaming a different kind of engagement with the hobby than I had been used to, in a real sense it is a different values system. I found this fascinating and rewarding.

A few cautions are in order. First, what follows are my own subjective impressions. I don’t presume these are everyone’s universal experience. Second, and closely related, these are generalizations. There will be exceptions and counter-examples to everything I say.

Last, none of this is prescriptive. I’m not trying to tell anyone how to enjoy their hobby or the proper way of playing with toy soldiers. I’m just writing to share a bit of my own journey, in the hopes it may be of some interest to others.

YOU START WITH AN ARMY

Hex and counter wargamers think in terms of, well, games. Generally everything you need to play a board wargame comes in a nicely shrink-wrapped box. (People even get testy when asked to provide their own dice.)

Figure gamers, by contrast, start with an army, meaning the figures themselves. These can be literal armies, such as enough battalions to field Frederick the Great’s at Leuthen (47 of them, plus 133 cavalry squadrons and 78 heavy guns). Or they could be a Viking warband composed of a few dozen figures. Often players choose to only buy and paint the army for a single side, relying on their mates to field the opposition.

Starting with the army makes for an interesting change of perspective. Because it’s literally what you bring to the table, it can largely determine what kind of games you will play. You can jump into Napoleonics with the French or the British, but maybe a little fresher to field the Spanish? Or the Hanoverians?

British light infantry in North America. 28mm figures from Warlord Games

Starting with an army also focuses your attention on the actual historical composition and organization of whatever force you’re mustering. How many battalions were in a regiment? How many regiments in a brigade, brigades in a division? Are you modeling a Union Corps? An 1862 Union Corps? Hooker’s I Corps at Antietam?

You need to make up your mind, because all of this is relevant to the figures you will purchase and paint. And your decisions, you will discover, will say something about your own interests and approach to the history.

How much do you care about modeling an actual historical unit present at a particular place and time versus a more generic force? How much research do you want to do? It’s very different from having the order of battle come to you on a die-cut sheet of counters to punch out.

By the time you’ve completed your army—the gluing if the figures require assembly, the priming and the painting, the banners and standards, the basing and flocking, the varnishing and finishing—it really does feel like your army. You know more about the composition of the Duchy of Warsaw’s infantry divisions than you ever thought you would, and you remember individual details of each and every figure that you labored over.

You array your men on the tabletop in front of you in parade formation. You admire them. You insist that your long-suffering partner admire them. You stand a little taller and address them as Patton might: “I will be proud to lead you wonderful guys into battle, anytime, anywhere.”

GAMES OF INCHES

A miniatures game is not a diorama with dice. This was a hard lesson for me because that’s what I thought I wanted them to be. But despite the often obsessive attention to realism and detail, the painstaking painting and craftsmanship, nothing on the table is ever quite what it seems.

Everything is an abstraction, a concession, a compromise. This is true even in skirmish gaming (where one figure equals one combatant) once you get into weapons ranges and movement rates that are practical for a typical tabletop. Unlike a diorama which is a single slice of frozen time, a miniatures game is something that is animated, alive. It’s a tiny world of moving parts. And what you see is not always what you get.

At 28mm scale, a regiment of 600 figures in a two-rank line would need around 20 linear feet to deploy. I can’t speak for you, but that’s bigger than my dining room table.

So, what do you do? You compress the ground scale and decide what the frontage of the unit is actually going to be. So now your regiment only takes up a foot of linear space on the tabletop. Fine, but then of course you can only fit a couple of dozen actual figures into that space, so one man must stand in for 20 or 30 or 50; your carefully painted figures are no longer individual actors each with its unique own personality, they are cogs in a game system.

Now what to do about terrain? A simple one-story house at the new ground scale might only have a footprint of a square inch. Your miniatures would be giants towering over the town! Keep the buildings at the same vertical and horizontal scale as the figures then? Well, we’re back to frontages, and your peasant’s hovel now has the footprint of a chateau.

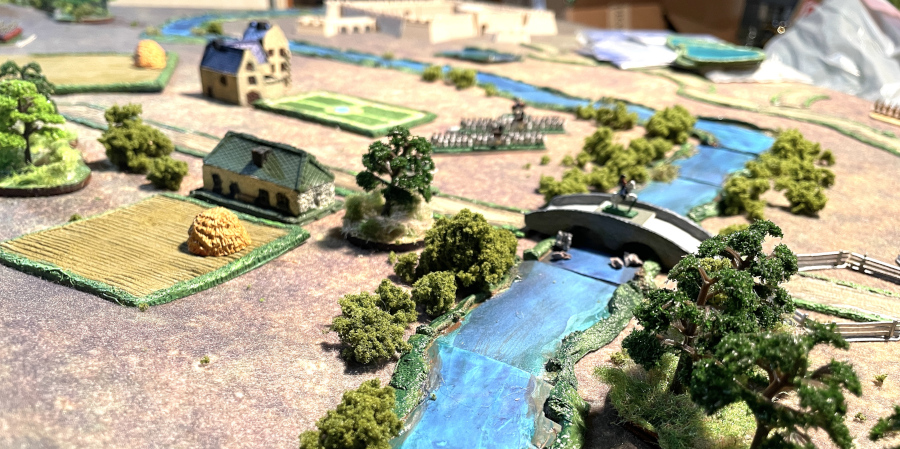

A tiny world. 6mm 18th Century figures

These are all very familiar contradictions to figure gamers. Most just shrug them off—it’s just a game, the play’s the thing—but others obsess over them. And again, short of one-to-one skirmishes with figures armed with stones and sticks—or playing on the floor of a gymnasium—there’s no real way of getting around them.

You learn what you can live with and accept, what looks right to your eye, and you let the rest go, or else you drive yourself to distraction. The point, though, is that the figures themselves turn out to be secondary to how the game is accounting for time and space, which in turn forms the basis for everything else in the rules.

So is that figure really where it is on the table, or is it just there as a concession to real-world (as opposed to game-world) physics? And what does that mean for the figures that are trying to maneuver around it? War really is a game of inches—it all gets pear-shaped very quickly if you think about it too hard.

This is no different of course from hex and counter wargames, which have their own share of abstractions and compromises to playability and practicality. But there the abstractions can sometimes be an asset: it’s a lot easier to feel like Ulysses S. Grant if you’re pushing tokens around on a topographic map, just as he would have been doing in his tent.

Figure gamers must not only accept but at some level embrace some basic contradictions in the laws of time and space. More than epoxy and glue, those contradictions are what hold their tiny tabletop worlds together.

GETTING TO THE POINTS

The vast majority of board wargames focus on recreating specific battles and campaigns, or else plausible almost-could-have-beens (like NATO vs. Warsaw Pact). Some systems, like the ancients series Great Battles of History, are notorious for giving players lopsided contests because history itself was rarely balanced. Miniatures gamers, by contrast, tend to have more invested in a fair fight.

Most often this is done by way of points, where two players are given an equal number to spend on the composition of the force they place on the tabletop. The explanation, I think, goes back to players owning their own armies: lots of good reasons to want to paint up some 1806 Prussians, but it’s not going to be much fun watching them get thumped by the French every time.

Amazing how they come to life. An indigenous woman for frontier gaming.

Whereas a board wargamer can be satisfied to say they’ve learned something about the history and put La Bataille de Jena back on the shelf after losing, the figure gamer is stuck with the figures in which they’ve invested so much effort and expense. So, as a consequence, there is much more interest in hypotheticals, in generic or representative actions, or in wholly imaginary ones (so-called “imagin-nations,” where make-believe fiefdoms and baronies field their retinues in elaborate fights of fancy).

The purest form of this approach is perhaps the ancients game De Bellis Antiquitatus (DBA). The composition of opposing forces is strictly regulated to produce forces exactly equivalent in value (12 “elements” per side, no more and no less). Following history is not the main thing: Macedonians can go against Saracens if the players are so inclined, as long as the elements are equalized.

The playing area is always of a set size. Terrain placement is equally arbitrary—there is no effort at recreating any historical ground. A game can be knocked out in an hour or less. Tournaments and conventions thrive under these conditions, much as with fantasy kindred like Warhammer or even Magic: The Gathering or for that matter, chess.

The contrast to a hex and counter mainstay like Great Battles of History could not be more stark. With boardgames, there is always something new and shiny to move on to.

Indeed, given the glut of titles on the market, many board wargames are played just once or twice, the players sampling them as though at a wine tasting. “Hmm, I like the overall system, it has a nice bouquet, but the activation mechanic is a bit too tannic and that combat subroutine is very dry, isn’t it?” Rinse, spit, and on to the next game in the overflowing intake pile.

On the contrary, miniatures players often play the same sets of rules continuously, with more or less the same sets of armies and terrain (what you and your pals have got between you). When someone paints up a new unit or faction, everyone is eager to get it into the fray. And when someone acquires a showpiece bit of terrain, of course you’ve got to design a scenario around it.

It all tends to make the gaming much more about what’s happening on the table, as opposed to what’s happening in the rulebook.

MISERY LOVES COMPANY

An inescapable part of figure gaming is the crafting. Painting up the figures certainly, but so much more besides. Just basing them is an art form all its own. Then there’s assembling plastic figures from spruesand constructing terrain and buildings, whether from foamcore, cardstock, polystyrene, paper, plastic, plaster, wood, or whatever else.

And that’s to say nothing of hairier stuff, like pouring resin and the new arcana of 3D printers and laser fabrication. No one can master it all, and there’s always the risk of the crafting overwhelming the gaming. It’s easy to lose sight of the forest for a handful of lichen-covered trees.

The good news is that misery loves company. Everyone has been there, swearing over the glue gun, fingertips crusted with flock. Miniatures players swap tips and tricks and favorite techniques, they kibitz and commiserate, and they share their successes and failures. If you’re fretting over how to pour resin into your dry-caulked riverbed without it overflowing the banks (and without contaminating yourself) there will be discussion forums and tutorials and how-tos, on blogs and on YouTube and Facebook.

Of course, this kind of mental overload is exactly what puts many would-be figure gamers off. It’s the time and expense of all the tools and materials, it’s the room to work in and to store it all in, it’s the sense that it’s all too fiddly or laborious or tedious or too much of a mess.

That’s how I felt too. But I also discovered this is a big part of how the miniatures hobby comes together. It all tends to be very supportive and encouraging, even, dare I say, nurturing.

You can offer suggestions, but it’s bad form to dunk on someone else’s work outright. This sense of collective purpose was wholly new to me from board wargaming. There, materials science rarely needs to progress beyond the optimal tension on a pair of tweezers.

It’s also frankly nice to be able to do something with my hands that is part of the hobby but not the playing of an actual game. Sometimes my head isn’t into rules and sometimes I’m not looking to be in a roomful of people, pandemic or no. But I can always pick up my brushes and paint or knock out another stand of trees.

Trying my hand at a diorama. Siege vignette from the English Civil War, figures by Warlord Games.

I’ll never be great at any of these things, but it’s not so hard to get good enough. “Tabletop standard,” universally understood to mean “looks okay to game with from about three feet away,” turns out to be a wonderfully accommodating phrase.

After my French and Indian War figures I started on some Dark Ages factions. And some English Civil War . . . I’ve experimented with 6mm and even 2mm. I have a growing lead pile and too many ideas for future projects. I still don’t own an airbrush, but I do have a glue gun.

Miniatures rekindled my interest in wargaming at a time when my game room was feeling stale. They helped me through a difficult personal stretch, lockdown and otherwise. And they surprised me with the amount of confidence and satisfaction I was able to gain.

Matthew can be reached on Twitter at @mkirschenbaum. All photos here are his, and have all rights reserved.

Thanks for de-mystifying the miniatures side of the hobby, Matthew. Enlightening. I have not ventured there, despite the siren song. I ‘craft’ a plastic model kit or two from time to time, or create playtest parts for hex and counter games, and I definitely feel a similar hands-centric relief, similar (maybe?) to what you describe (sans skill – amazing photographs!). And the ‘it’s good enough for the table’ attitude towards craft quality is wonderful. But I really love the idea of people coming together with the components they have, plunking them down on the table, and making a game of it. You have Prussians? I have French. Huzzah!

Thanks Jeremy, that’s it exactly!