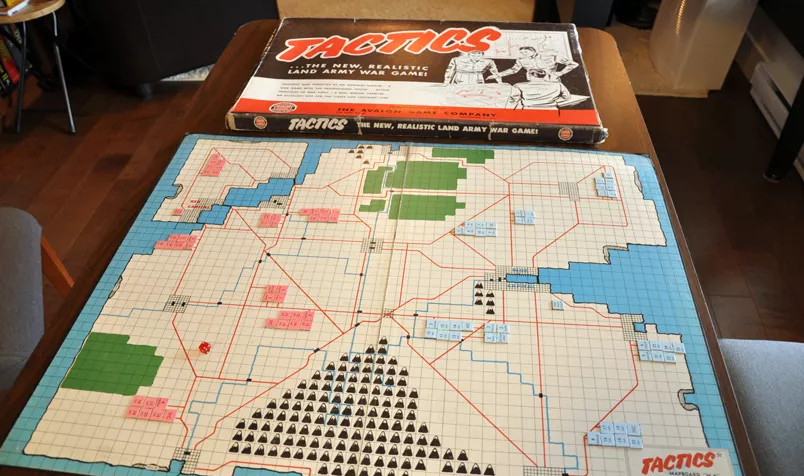

The following Conflicts of Interest Online article comes from Non-Breaking Space, the defender of orphans and widows, defenestrator of conventions and harbinger of the post-grog. They design games focused on the human impacts of modernization. Their latest design, Cross Bronx Expressway, is currently on GMT Games’ P500. (Featured image of Charles S. Roberts’ Tactics from @klaytonz on Board Game Geek.)

War is personal

For a while, I chose not to engage with the idea of war. I had trouble reconciling the emotions it would bring up. Conversations as a kid with veteran relatives. Dark, dark stories that start “What you know ‘bout?”, and then go from the most common thing, like a glass of water, to the most graphic depiction of violence you have ever heard, punctuated with “Yeah, you don’t know ‘bout that.”

They were not a part of any legacy. What drove them to service was not patriotism, honor or love of country, but perhaps one of the most common motivations for enlisting—limited opportunities. The idea of war is different when you come to it as the answer to why that relative is a little off. “Been like that since he came home,” you hear, and you do everything you can to avoid it happening to you.

The trauma of service does not end with service. It often extends through loved ones, leaving marks that might take generations to heal. My perspective of war, filtered through the lens of the violence it seeded in my family, made it hard to consider objectively. Nobody can.

Any conflict is viewed through the subjective lens of one’s relationship to it, whether through personal involvement, the stories of others (both real and imagined), the media, or even complete ignorance. We view the history of conflicts based on the political alignments within our society, filtered through the lens of its relationship to the society in conflict. In this way, regardless of intentions, the mere presentation of history, relative to the society in which it exists, is propaganda.

The difficulties I had reconciling war were actually difficulties reconciling the societal propaganda that surrounds it with the realities I experienced through loved ones.

Maybe you’ve been brainwashed too

It is a heavy word, propaganda. I use it here to define any distributed medium that promotes a particular ideology. How one views propaganda is tied to how the individual orientates themself to the ideology presented. If one is in full agreement with the ideology, it may seem like common sense, hardly propaganda at all.

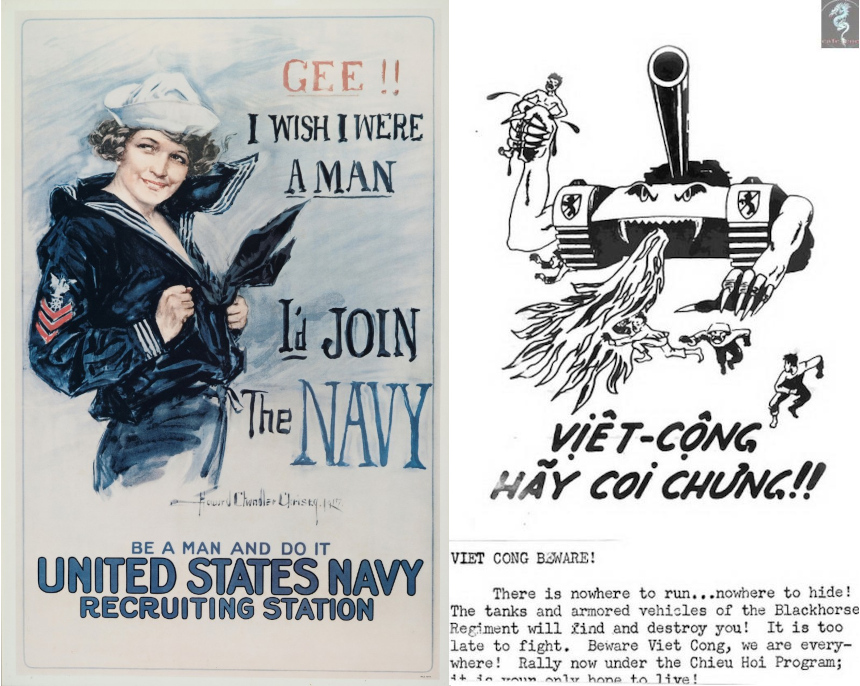

A couple of examples of propaganda posters. (Naval History and Heritage Command, Reddit.)

If one finds the ideology offensive, the propaganda and those who would spread it might seem obscene. In both cases it is still propaganda. We just accept and often seek out the propaganda that supports our biases and beliefs.

That propaganda plays an important role during times of war is easily understood. The political will of belligerents can be a deciding factor in a conflict. Propaganda to build support for the fight or weaken the will of opponents is tactically important.

That propaganda plays an equally important role in the post-war situation can’t be overlooked. It is at this time that the dominant ideology is reified as history. The stories that are told over and over create the public myth of the conflict.

History is not just written by the victors. History is not just written; it is carried forth by survivors of the conflict. The stories, known and unknown. The whispers and rumors. The myths and the legends. The trauma and pain. Official histories will always lag behind the lived histories that perpetuate in real time.

It can take decades, if not centuries, for a society to be far enough removed from a conflict to even approach the official history “objectively.” Even after some reconciliation of the past, when a society has moved on from an older ideology, it will still approach history through the lens of the new one.

This retelling of history in support of a present ideology is what makes history political. Even a “pure” presentation of facts is still relative to its context, and often it is what is omitted that shapes that context. Details abstracted away to serve a clarity of purpose.

Choices of what gets abstracted come from individuals with their biases. These biases exist within a societal context that transforms what they produce into propaganda. This happens, regardless of the individual intentions.

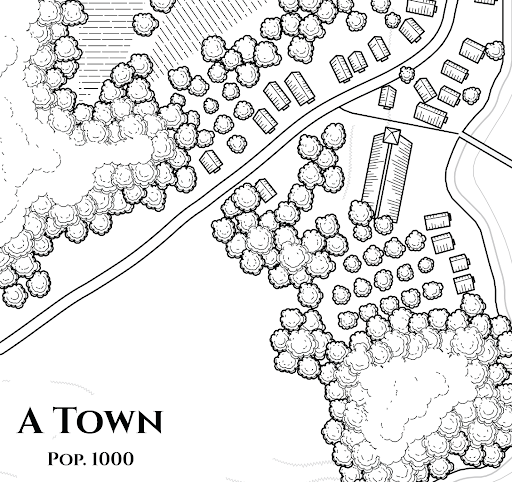

A town

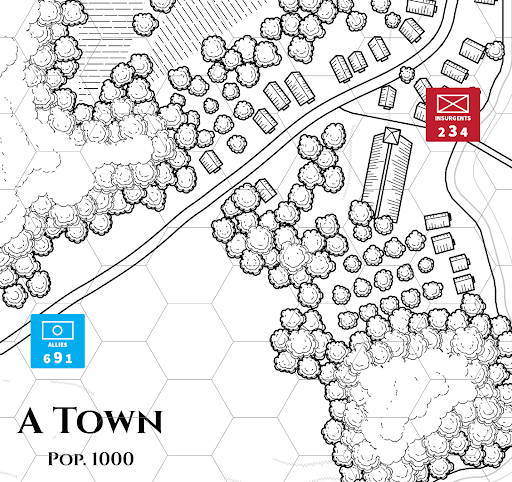

A town. (Map from https://watabou.github.io)

Imagine A Town of one thousand people, caught in the middle of a conflict. There are at least one thousand perspectives of this conflict, each one of them lived and true.

Two decades later, the leading book on the conflict cites the reports of a government official who interviewed three out of the one thousand people in A Town. In the footnote of the leading book on the conflict, the author bases their conclusions on the official’s one-paragraph summary of the civilian interviews they conducted leading up to the start of the conflict.

“There was an aggression in their tone when responding to my questions. Often they used the same rationale heard in the north where the insurgency is firmly rooted. If something is not done to stop this spread it will surely grow into a bigger problem. It may already be too late.” – A Town Official Report

The author of the leading book on the conflict uses this paragraph summary of three interviews to describe the population of one thousand people in A Town as insurgents. That term places those thousand in a broader context, defined by the views of the society the author of the leading book on the conflict was born into.

And that society is not where A Town is located. The complex dynamics of those thousand lived and true perspectives has been reduced to a label based on a paragraph summary of interviews with three of them, marginalizing the agency of those thousand people to fit into the ideological framing of the society where the history is being read.

This is all hypothetical, and perhaps you see holes in its presentation. Take the interviews. Surely, the leading scholar on the conflict would not stop at a summary. The leading scholar would go back to the source and talk to those people.

Unfortunately, those thousand people were killed when A Town was shelled to eliminate the insurgent threat. The tapes of the interviews were destroyed when the municipal buildings caught fire. All that is left is that one-paragraph summary to account for those thousand people.

History in context

History is an incomprehensible beast, and our understanding of it is always incomplete. We learn it in the abstract, because that is the only way it is digestible. Our abstractions are shaped by propaganda, and the more narrow that shape the more it trends toward dogma. We cannot know all of any history, but we can be broad in our investigation.

My barriers to understanding war were narrowed by the view I took of it early on. As I got older, the unanswered questions itched. History was incomplete without answering those questions, or at least approaching them. I needed a way to forego my misgivings to make the topic of war approachable.

This meant putting war into its broader context as history, not just as an affair of the military, but one which affects the whole of society. Contextualizing requires a diversity of perspectives not just in topics, but per topic. The socio-economic factors, the politics, the impacts on the affected civilian populations. By looking into each of these, and taking into account the perspectives that come with them, a detailed investigation into history can cut through the propaganda.

It takes work. There are many academic tracks for doing this work, but even lay people need to as they get deeper into their particular historical interests. It is not enough to hold to a narrow perspective of history without ever putting it in the broader context. Any history presented as such is not just propaganda, but dogmatic propaganda.

Which brings us to wargames.

Contextualizing the roots of modern wargaming

Wargaming as a professional practice goes back centuries. Military leaders have long employed games with hopes of gaining practical insights before committing soldiers to battle. It is a tradition that continues today within militaries across the globe. The shapes and forms it takes differ from the early kriegspiel days, but the lineage, particularly in purpose, is very clear.

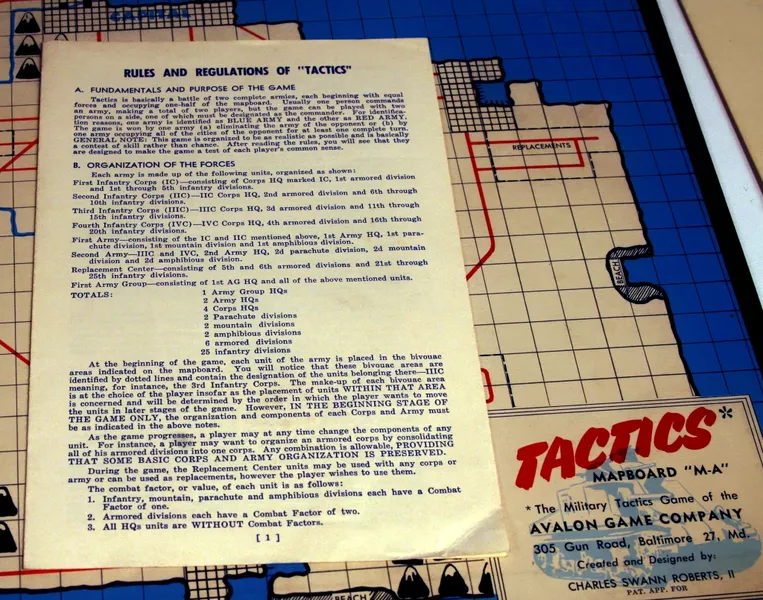

Modern hobby wargaming is usually dated to Charles S. Roberts’ 1954 game, Tactics, which simulated a conflict between two fictional countries. Roberts designed Tactics as a way to learn about the military strategy that he hoped to make into a career. Fate would remove the military option from his career path, but designing and publishing Tactics left him motivated to start Avalon Hill, one of the preeminent modern wargame publishers.

This places the birth of modern wargaming in a very specific context. The United States was a decade out of WWII, and years out of the Korean War. The U.S. military was itself modernizing its approach to wargaming in response to the new landscape of the Cold War. The global view of a young infantryman looking to pursue a career in the military in that context is a very specific perspective.

The “Tactics” board and rules. (Image from Ed Bryan, uploaded to Board Game Geek by The Maverick.)

The red and blue sides in Tactics are fictionalized, yet coded. We can think of it as a Cold War game, despite its fictional setting, and trace a long tradition of wargames projecting the Cold War culminating in conventional kinetic warfare. What can’t be overlooked, however, is how this perspective set up the framing for modern hobby wargaming as a whole.

Parallel contexts

Modern hobby wargaming in some ways has paralleled the modern professional military use of wargames. Hexagon maps and Combat Results Tables became standard across both contexts because of how close their evolution was intertwined. The desire to model realism into the games was shared across contexts, but the purposes, and thereby the standards, were quite different.

Hobby wargames often presume the same affordances of professionals, despite existing in an entirely different context. Where the choices presented in a professional wargame affect real-world decisions, choices presented in a hobby historical game only affect real-world impressions within a niche. The impact of the latter may seem smaller, but it is not something we should dismiss.

In professional wargaming, the intent and ideologies are explicit and for an expressed application. Within that context, abstractions are used to focus the game toward a practical output. A game may focus exclusively on the military domain of the conflict to test force strengths and deployments, but it happens in a broader context informed by the other domains of the conflict as well. The social, political and economic parts of a conflict are accounted for by the participation of professionals who specialize in these non-military domains. Their feedback is used to scope the wargame design, constraining it to practical outputs.

Pulling the framework of professional games out of context for hobby use puts the responsibility for contextualizing those social, political and economic domains on the designer and the player. This leads to either the omission of these domains or abstractions. In hobby gaming, that can get murky, as abstractions tie directly to player agency. Where the professional game is concerned with the accuracy of the output, historicity and accuracy are often secondary to the player experience for commercial hobby designs.

Offsetting this market driven approach is the desire within hobby wargaming to present as “realistic,” which can also be traced back to the original marketing of Roberts and Avalon Hill. Even in the early years of modern hobby wargaming, research played an important part in depicting history through the games, yet primarily through the military lens. Orders of Battle are a good example of this.

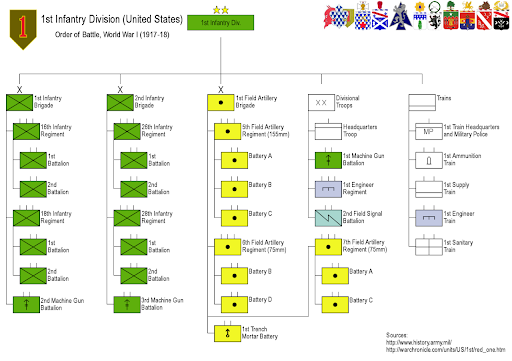

An order of battle for the U.S. 1st Infantry Division in WWI. (Wikipedia.)

Orders of Battle (OoB) are the sourcebook for many modern wargames. These detailed lists, quantifying military units engaged in a particular conflict, are cited when designers model the units represented in their games. Logic holds that if the OoB is modeled properly, the rules for the units will constrain the players toward outcomes that can be considered historically possible. A similar approach is used for professional games where real weapons and equipment are modeled, allowing for projections and insights on how choices in force deployments and actions can affect outcomes.

In the professional case, modeling the destructive power of an artillery shell on its own answers very specific questions. The other questions (civilian risk, adherence to global policy, effective costs) may be asked and answered outside of the military wargame. In the case of hobby wargames, the OoB often stands on its own, leaving it up to the players to contextualize and answer those questions, or not. Too often not.

A Town, reprised?

Remember A Town? Imagine those one thousand people abstracted into a single counter. They are given a strength value shaped by the prior definition of them as “insurgents,” and data sheets about the general military capacity of insurgents in that area at that time. This counter sits in a town hex which is in range of an artillery unit.

The A Town map with counters.

In a previous turn the official (not represented in the game) traveled to the hex and interviewed three of the people in that counter, before returning to the municipal building in the adjacent hex. This turn, the player controlling the artillery unit rolls a 5 on a six-sided die, which removes the insurgent counter from the map.

Two turns from now, the artillery unit will target the municipal building, starting the fire that burns the recordings the official made. The official will survive to summarize their work somewhere not on the map.

The war for war

Clearly, this writing is propaganda too. The ideology it presents is one that supports recent movements to broaden the way we think of wargames.

“What is a wargame?” is a question that has been asked for well over a decade now. Literalists say “war = military,” and thus wargames are primarily concerned with the military domain. Other categories have emerged such as “conflict simulation” or “historical games,” which widen the scope to be more inclusive. They do not, however, address the fallacy that “war = military”.

A hallmark of this literal perspective is the cry to “keep politics out of wargames”. It gets contradicting support from things like the “by other means” cliche which will usually equate politics or economics with “war by other means”. A lot of this comes to wargames through the military influence noted above.

The military as an institution is thought to be apolitical. Thus, it is believed that the decisions made by the military can be examined on their own. As has been detailed above, there is a lot of nuance to this perspective, but it has been carried over into hobby wargaming quite literally.

Hobby wargaming’s call to keep the politics and other domains out, shapes the propaganda that the games themselves become. Since the birth of modern wargaming, we’ve seen The Lost Cause, Clean Wehrmacht, Noble Savage and other troubling perspectives promoted through wargames by singularly focusing on the military domains of conflicts.

Not all of the promotions of these ideas have happened intentionally. And it would be wrong to attribute these views to the hobby itself. It is important to recognize, however, that literal approaches, which only accept a narrow view of history, are what facilitate the promotion of these harmful ideologies.

As a fan and designer of wargames, this is not meant as an indictment. It is meant as an opportunity to address these issues. Even more, the market is demanding it.

In the past few decades, more and more players are coming to wargames not from an interest in the military, but from interests in history. That has led to an increase in games that contextualize war beyond the military. Designers have created new mechanics and systems for presenting this history with great success, challenging previous perspectives of what constitutes a wargame.

The response among some literalists has been to entrench in their strict definitions. This is gatekeeping, and if you’ve been following along, you’ll note here that gatekeeping is also propaganda. Even more, in this instance, closing the gates does as much, if not more damage to those within them as it does to those on the outside. We all need broader contexts.

Doing the work

In my ongoing efforts to understand my trauma, I had to come to terms with war. I had to contextualize the socio-economic realities I understood war through, with the military realities that helped inform them and the political realities that shaped them. Wargames have played an important part in this process, as understanding the command decisions as simulated through military-focused games has helped broaden my perspective of the culture of war.

Some might say that books are better for this purpose than games. Clearly, I read books as well. I also study archival records, talk to veterans, and conduct a multitude of other research activities to help provide as much context as I can.

Games have played a significant role in that. Their interactivity allows for perspectives that just cannot be found in books, even in the books referenced by the games. Also, books are not infallible. They fall into the same propaganda traps that games do, there are just a lot more of them.

There are often multiple books from multiple perspectives, analyzing a single conflict. There may be two games on a particular conflict, both focused on the military domain. For some conflicts, two is too generous. We need more games.

To be fair, there are more games contextualizing conflicts across domains than when I was first exposed to wargames almost 40 years ago. There are full games on the politics and economics of conflicts. There are games which don’t shy away from the civilian impacts and put some agency in the players’ hands to account for it. There are games on conflict from the civilian perspective. There are games on Partisans that were previously only a single counter in a hex-and-counter game.

Yet, and still, these games represent a small percentage of wargames. And for any particular topic, that percentage will be even smaller, if not approaching zero. Taken as a whole, this bias towards the military domain puts wargames squarely in the realm of propaganda. Debates over the term itself, and attempts to restrict its definition to only account for that single perspective, push that propaganda towards dogmatism.

Some might read this and become even more entrenched in their position, citing the long history and tradition of wargames as evidence that theirs is the proper definition. Others, perhaps a more silent but growing minority, will note that we are approaching a tipping point. With over half a century of history in the hobby, there is room for reflection and charting a path forward that broadens the scope to include more contexts and provide a better understanding of the historical impacts of warfare through the games we play.

There is still a lot more to do. The best way to do that is to ask the questions, interrogate the presentation of history through games, and elevate those perspectives that give voice to all who participated in and were affected by the history.