This article is by Maurice Suckling, about the design of his currently-on-Kickstarter Crisis: 1914. Maurice is an Assistant Professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, NY, where he teaches and researches storytelling in games and historical simulations. He has been writing for video games since the late 1990s (Driver, Civilization VI, Killing Floor 2, Borderlands: The Pre-Sequel). His board games include the CSR award-winning Chancellorsville: 1863 and the recently-Charles S. Roberts-nominated 1565: Siege of Malta.

The origins of Crisis: 1914

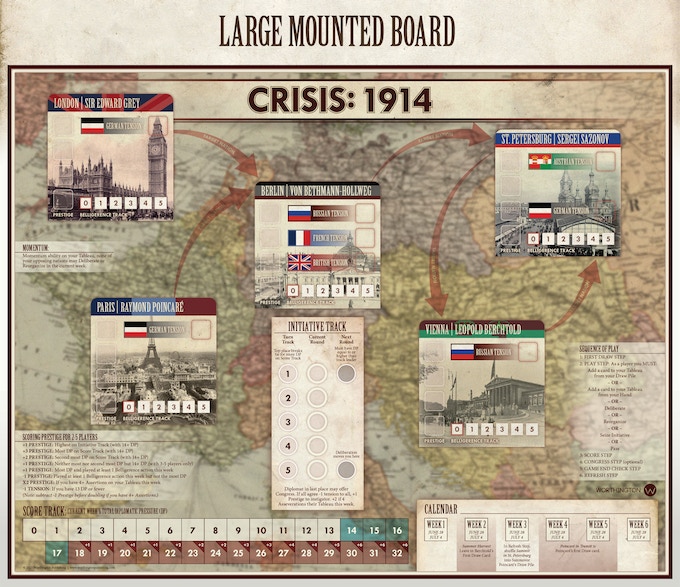

Crisis: 1914, a game about the July Crisis— the diplomatic crisis that gave rise to World War I—will be published by Worthington, and is on Kickstarter through Friday, July 28.

This seems a good time to reflect not so much on the completed game itself (although that’s a topic I’d be happy to explore another time), but the path taken to get there. And—‘Merlin’s mushrooms!’ as my six-year-old daughter will sometimes say—it has been a long and meandering path; one that may resonate with many designers and might intrigue many players of conflict simulation games who might wonder how these things get made.

It might well be true to say that a design is never really finished, you just get your hands slapped away while it gets put in a box. Yet it’s still possible for a designer to feel as if a game reaches a certain stage where they can be happy with it—at least sufficiently so. Indeed, in this particular case, there was no time commitment to a contract-wielding publisher to obey. I got it to where I wanted and any further serious design iterations (and that’s a separate topic) were going to push it into another design space entirely. So it was time to find out what people thought about what I had and let it go.

Looking back, it can seem rather obvious what paths I might have taken to get where I ended up. But this is deeply deceptive, because it obscures the truth that when I began I wasn’t entirely sure where I was trying to get to. And making sense of that design journey necessarily pulls focus onto a narrative that hinges on what Crisis: 1914 now is.

“[T]he end makes a concord with what has preceded it,” as literary critic Frank Kermode tells us (Kermode 2000, 178). The word ‘journey’ isn’t even the right one, because it implies a clear destination, when the destination was anything but clear. I wasn’t on a journey. I was in a process. A process of discovering what journey I was on, and if I figured that out I’d find the destination. And only at that point could I actually begin the journey to get there. See?

All that said, I’m now going to attempt to frame the game that became Crisis: 1914 in a narrative that makes it possible to see something of the process from a satellite’s perspective, rather than the earthworm’s perspective I had for much of the last 40 years. So buckle up, we’re going back in time.

Starting with Diplomacy

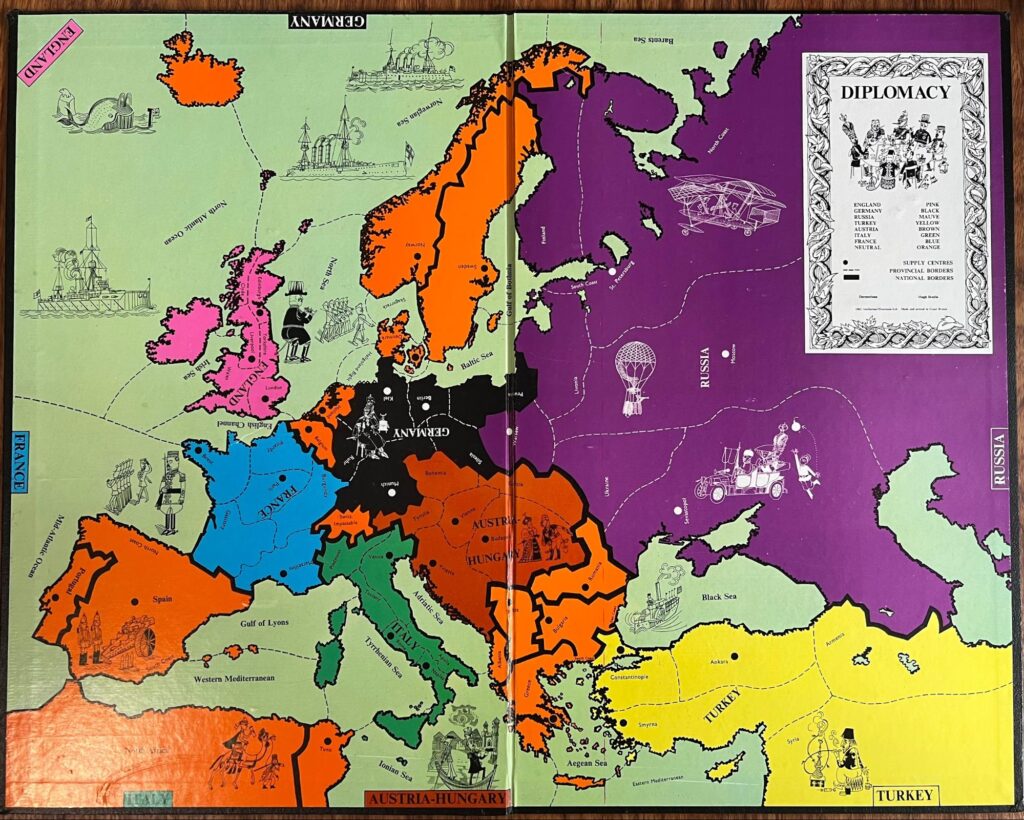

It began when I was first introduced to Diplomacy in the early 1980s. I was struck by the elegance of the design (so few rules, so few pieces, so much agency), and by the historical setting in pre-World War I Europe. I was fascinated by the idea of a game about diplomacy before any war might occur.

It began with Diplomacy…

Of course, Diplomacy almost certainly entails opening moves that effectively immediately set wars (or one large, messy war) in motion. But what would a game about rising diplomatic tension allowing for the possibility of a major war—but rewarding its avoidance—be like? That is to say, what would a game about diplomacy without war as its focus be like?

Even the box art drew me in…

So began many years of doodling area control maps of the world in the Nineteenth Century. My thinking ran along the lines of “Perhaps you have to set a game at the beginning of the imperial era to build to the tension caused by colonial rivalries.” In effect, what I was really doing, but didn’t realize at the time, was making a series of global Diplomacy variants, none of which developed very far.

A c. 1986 prototype map.

Jim Dunnigan and Origins of World War I

This cycle continued for several years, with my interest being sustained by a game I found in a book my ever-thoughtful mother bought for me in a sale for just £2.95: Sid Sackson’s Gamut of Games. In a book which seemed to be largely about games with regular playing cards and abstract strategy board games, which I had almost no interest in, was a game called ‘Origins of World War I’. It was designed by a certain ‘James Dunnigan’, a name which meant nothing to me as an early teen. But the theme sure spoke to me.

The book was first published in 1969, and the second edition came in 1982, and I have the UK Hutchinson paperback edition from 1983. According to BGG, Dunnigan’s design dates from the 1969 edition of the book. This means before I was even born Jim Dunnigan had tackled the topic, and seemed to have had the last word on it that was worth having. Perhaps a familiar feeling for many designers tracking the work of Jim Dunnigan.

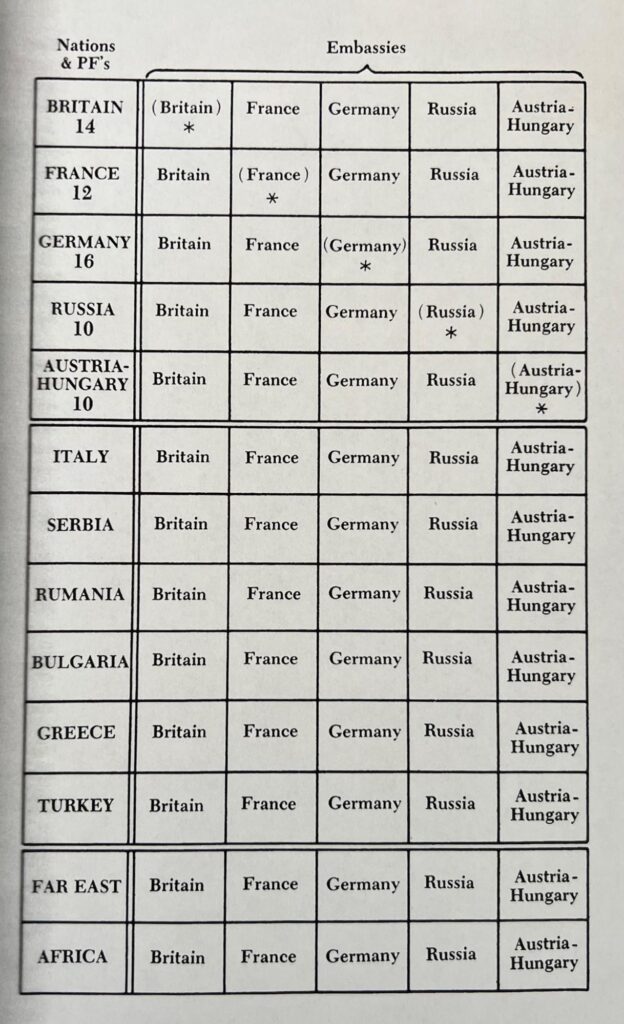

Origins of World War I was a 5-player game about securing treaty rights—which was done by applying Political Factors (PFs) into embassies. PFs were really akin to what later games like Twilight Struggle would call ‘influence points’, and were essentially similar to strength points in a more conventional wargame. Secure enough of the highest valued rights and you won the game.

The board for Jim Dunnigan’s Origins of WWI. Players place poker chips (Political Factors) on embassies to claim treaty rights.

I never did play it with anyone else, but I played many times solo. It scratched a certain itch, but the means by which treaties were secured was through a conventional-looking combat results table as you worked with, or against odds and rolled a D6 to try to defeat other PFs in the embassies you targeted. The end result was I didn’t feel like I was playing at diplomacy—it was more like combat with a set dressing of diplomacy. Perhaps there was no other way to do it? I guess it’s Jim Dunnigan’s world, and we merely live in it.

Origins of World War I – players win victory points according to which treaty rights they secure (or deny).

Pax Britannica

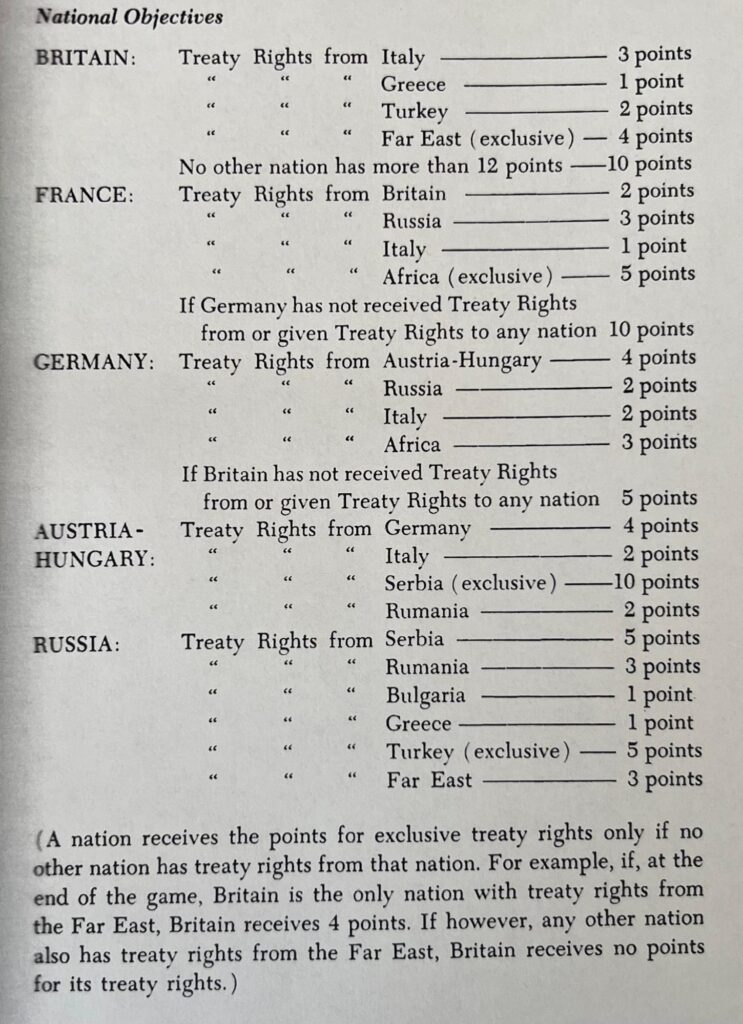

My interest was further sustained by 1985’s Pax Britannica, which I bought from my then local games store in Oxford, UK. That store, called The Gameskeeper, was run by two Americans who were friends with a Reiner Knizia and always seemed to know what was happening in the hobby.

Pax Britannica, designed by Greg Costikyan and published by Victory Games, on the face of it, was exactly what I was interested in. It had expanding colonial ambitions and rising imperial tension, leading to the game ending if a world war actually broke out. I remember an extremely large paper map, lots of bookkeeping—with actual ledger pads that came with the game—moving military units, and purchasing them. But there wasn’t much cut-and-thrust of tense diplomatic exchanges.

The Pax Britannica box cover.

Perhaps it was uncannily accurate, and this is exactly how imperial civil servants felt. It’s possible that the game really was what I was looking for. But it got one play before my games-playing older brother went off to university, and it never got another real chance.

Perhaps if I’d been more patient with Pax Britannica, I would have loved it and never tried to design anything on this subject matter again. But that’s not how the earth turned for this earthworm. I just felt like it hadn’t really spoken to me in the way that I’d hoped, and suspected at least half of that was my fault.

Exit, Return, and Concert of Nations

In fact, a few years later, I largely fell away from the hobby entirely. I was at university, games seemed to be getting bigger and longer with more pieces, design sensibilities seemed to be moving further away from the “few rules, few pieces” concept I’d really engaged with, and life got busy.

In the early 2000s, with a video game development career underway, I started to get drawn back into the board game hobby. Some of the first games to do this for me were relatively simple games, such as Battle Line (2000), Condottiere (1995), and a little later, Pandemic (2008).

Battle Line and Condottiere.

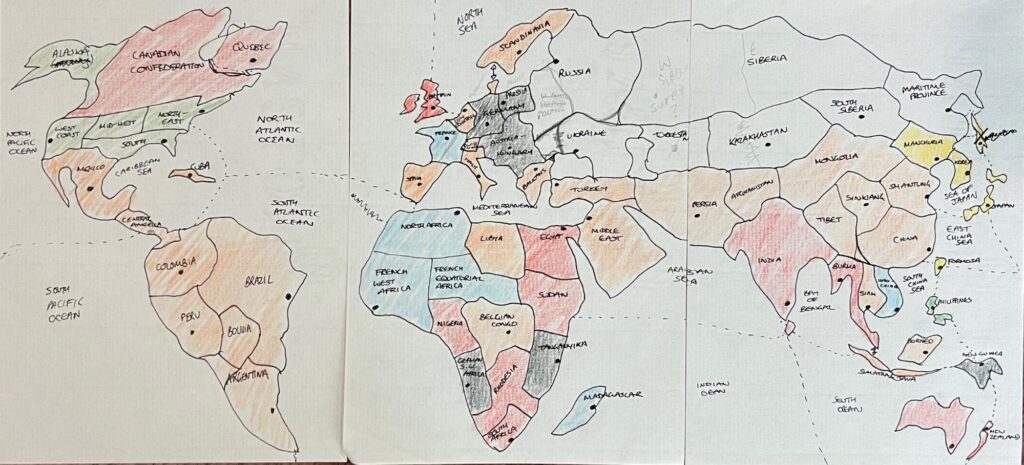

I found myself drawing area control maps of the world again, returning to the same kind of place I had about 20 years earlier. (Like I said, this was not so much a journey as a process.) I was wondering how to make a game about rising imperial tension that wasn’t exactly a wargame, more of a sort of tension simulator. Since I wasn’t really interested in the acquisition of empires, I started exploring an idea that saw global powers already with imperial projects underway, but still with some runway leading up to 1914.

I wondered about starting the runway in 1871, at the birth of the German Empire, which really set the whole geopolitical dynamic in motion. But I thought, perhaps, that was too much runway. So I pushed the start point up to the early 1880s, so there was still plenty of real estate for players to get heated over (Africa, Asia, the Balkans). Players would take on the roles of Britain, Germany, France, Russia, Italy, Austria-Hungary, the USA, and Japan.

Taking something from Pandemic, I had a simple AI game deck represent revolutions, internal political turbulence, and uprisings. Players were tasked with trying to contain these problems whilst also trying to sustain projections of imperial might. One of the kickers was that placing troops in regions to control rising tension would be a short-term solution which would have long-term consequences of generating tension in the future.

I didn’t know it at the time, but about 10 years later this idea would take hold in my Rebellion: Britannia (currently on P500 with GMT, co-designed with Daniel Burt) a game about the problems Rome had in first-century Britain attempting to control the indigenous tribes. There, it became a central element for the Roman player to try to juggle. Roman control of regions causes British political tension to spike, out of which the Britons form warbands, causing Rome to march in legions to destroy them. That causes the warbands to either stand and fight, or to dissipate back into tension, which legions are impotent against and it takes political levers to address.

This is a (slightly blurry) picture of what I was developing, whilst living and working in Australia, around this time. It was called Concert of Nations, a title I’d used in at least one but perhaps more versions of games I worked on in the 1980s.

A Concert of Nations concept from 2014.

There were Tension Tracks to register how good or bad a job the players were doing at controlling political turbulence, with everyone losing if it reached a certain level. But ultimately, it dawned on me, what I was building was a game about imperial expansion, where control of tension really meant suppression of anti-imperial perspectives. And this really wasn’t what this earthworm was in the soil for.

I pushed the start point up again to 1900—like Diplomacy—rebuilt the game, played it, and the same thing was happening. Now it was still about empire building, but it was just an accelerated timeline. Things stopped again.

A Concert of Nations concept from 2014.

Further inspirations, and Freeman’s Farm: 1777

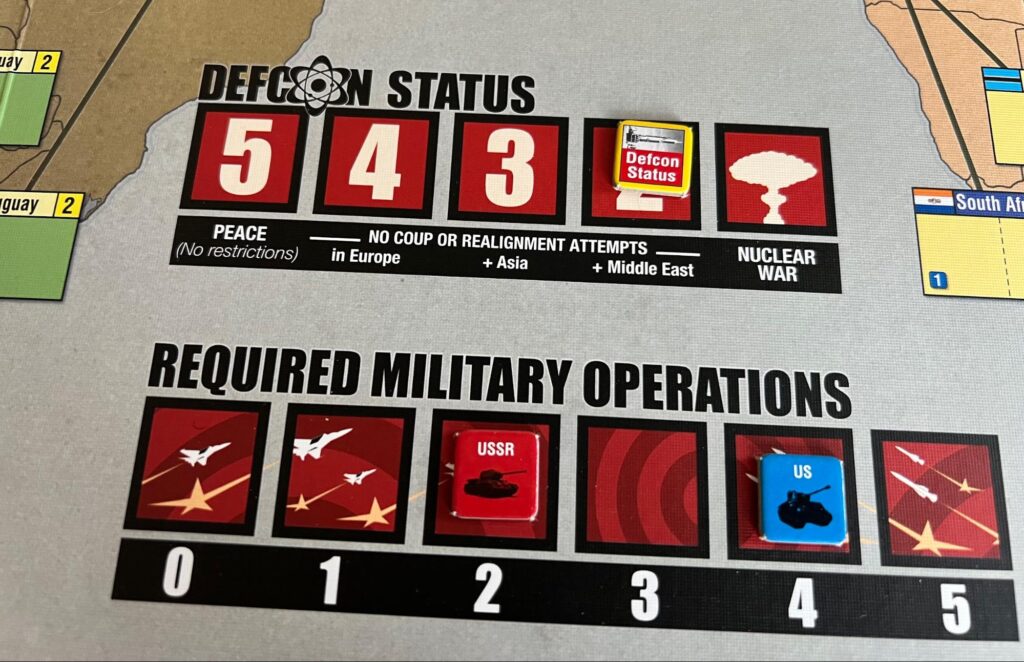

I played Twilight Struggle (2005)—although I didn’t play it until 2014—and loved it. I was intrigued by the way the required military operations pushed players towards the game ending state of nuclear war, but if players didn’t do it they were gifting the other player victory points.

The Twilight Struggle required military operations track.

I played Mark Herman’s Churchill (2014), and loved it. This delivered the kind of high-level strategic/political perspective I’d been missing in my games but never really realized until I played it. Here was a way to model negotiations that seemed strangely obvious now that I saw it. I started making a game about the Treaty of Versailles (this is another topic).

I took a job in Upstate New York teaching games in college, and completed an online Master’s program in Global History from Birmingham University, designed a board game called Freeman’s Farm: 1777, which found a publisher (Worthington) far sooner and who was far more enthusiastic than I’d ever thought possible.

Back to pre-WWI, and Peace: 1914

Discovering I was now a published board game designer, I found myself thinking about what to do next, and returned, along with a couple of other ideas, to the pre-World War I topic. I realized (again/more clearly) that what I was really interested in wasn’t the making of imperial projects, it was the diplomatic situation leading up to World War I. So, I suppose I must have reasoned, why not pull focus directly onto the July Crisis? Start the game on June 28 1914, and take players through the crisis as they attempt to address it?

And, then, why not have them try to work together to avert the war? Co-op games are great! What a satisfying inversion of a story about war starting to see if you can stop it! It would be an alternative take on history, but perhaps a refreshing one—one where the “great seminal tragedy of the twentieth century” as American diplomat and historian George Kennan had called it, could be imaginatively un-made. Maybe call it Peace: 1914!

Peace: 1914, or Crisis: 1914 – the alternative history co-op version.

That led to a version of the game which was fully co-op, with players working against the hawks in their own governments to try to stop everything from blowing up. That game spent a couple of years in development with a mechanic I was especially pleased with whereby secret conversations could take place which would prevent tension from bubbling over publically, but it had to be addressed before it did so with a vengeance. I ended up showing it to newly-made friends Jason Matthews and Kevin Bertram on a visit to DC.

Jason Matthews (l) and Kevin Bertram (r) testing an earlier version of Crisis: 1914.

The game largely worked. Yet it also didn’t. I just sat on it for a bit until I could pinpoint what the problem was (again, process, not journey). I’d let my fantasy about stopping war get in the way of the actual history.

The reality was none of the key actors in the July Crisis, except Britain’s foreign secretary, Edward Grey, actually had a primary motive of stopping the war (and even that only insofar as that war might get large enough to involve British interests). Everyone else was caught in some version of what game theorists call ‘chicken.’ And Grey, too was caught up in this, and the lack of clarity in the British position in relation to France and Russia most likely made things far worse than had Grey been more forthcoming about this—not only to Germany but also to his own cabinet as well.

The net result was I had a game which really wasn’t about the motives of any of the key actors, and I hadn’t really engaged with the July Crisis as a topic at all. I’d actually bypassed it. I showed it to some more playtesters who found it boring. Ouch.

I felt like I’d blown it. I’d failed at something that had been niggling at me since the early 1980s and it was probably time to put it away and do something else. I was no Jim Dunnigan and had come nowhere close to matching something he’d done in 1969. Perhaps I wasn’t really a board game designer at all, and should go back to writing video game stories.

Taking on the July Crisis, and a “not-game”

A pandemic, ConSim Game Jam #1 (out of which came what would be Rebellion: Britannia) and a new child happened. And I thought something along the lines of “Instead of bypassing the July Crisis, what if I tackle it head on? What if I align the players with the motives of the key actors, and keep the game of chicken central to whatever players do?”

This sounds obvious in retrospect. Ask the right question early enough and you get closer to the answer faster. And then you can at least see where you need to get to!

So, now I contemplated throwing everything away and starting again. Maybe the game was still about not letting the war happen, but you were trying to win by navigating avoiding war while also somehow pushing your prestige up.

Twilight Struggle’s required military ops had perhaps been fermenting in my brain. I had a nascent notion of two concepts—rising prestige and rising tension—being inextricably linked. Why else would you be prepared to risk pushing tension up?

I took my young son on numerous walks in his stroller talking him through my thinking. But, as my son’s silence seemed to attest, I didn’t really have anything at all. What I had was a ‘not-game’—a game I wanted it not to be. I wanted it not to be a game about imperial expansion, and not to be a co-op game that bypassed the history with ahistorical motives. And a not-game turns out to be almost entirely indistinguishable from not a game at all. This wasn’t impressive progress since 1982.

ConSim Game Jam #2 inspiration

Then ConSim Game Jam #2 happened. I recall my finger hovering over a keyboard button to exit the event moments before it started. None of the people I’d hoped to form a team with were available, I didn’t know anyone in my prospective team, and a game jam weekend is brutal with small children, and there had only been one of them the first time around…

But I didn’t hit that button, and made some new friends (Nathaniel Berkley, Bill Sullivan, and S. P.), and we made a game about the Treaty of Portsmouth which ended the Russo-Japanese War, provisionally called Peace 1905. That was a negotiation game where you won by securing the most victory points connected to issues in the treaty. But every time you won you were likely causing tension, pushing your opponent closer to walking out. And if they did walk out you would lose.

Instead of your cards being different personalities, as in Churchill, your hand of cards would be made up of different “positions.” Those would range in value from the zero points of an “Acquiesce” card to the four points of a “Threaten.” The higher the value, the more likely you were to win the issue in the treaty and to have that treaty written in your favor. But, here was the kicker, the higher the value the more likely you were to spike tension and so to lose.

72 hours isn’t much time to make a game. (Trust me.) But it likely helped that some of these ideas about the relationship between diplomatic assertion and the resulting tension had been swimming around in my head for some (considerable) time beforehand, albeit perhaps without any clear direction.

Peace 1905 – a development build on TTS, early 2023.

We ended up winning the game jam, we continued developing it, and we recently signed a publishing contract with Kevin Bertram at Fort Circle Games. I think it’s something rather unusual and rather special. We shall see… (That too is a topic for another day.)

Back to WWI origins, and more inspiration

Shortly after the game jam diversion I was sifting through the pieces of my not-game on the July Crisis while chatting with Jason Matthews, one of the judges for the ConSim Game Jam #2. He said how much he liked Peace 1905, and we fell to talking about the prototype he’d played with Kevin Bertram in DC. This is the conversation on Facebook:

Jason: I liked your origins of WWI game. Tbh.

Jason: The thing that bothered me about it is that I don’t think that preventing war was the central aim of many of the actors.

Maurice: Yeah – it’s what bothers me too. It’s alt. history. It’s – what if we took the set-up, the situation, and the governmental pressure, but then ascribe the major actors the motivation to stop the war. This wasn’t their real motivation. It was more complex.

Encouraged by comments from Jason and the other judges (Mark Herman and Candice Harris) about the ConSim entry and by Fred Serval banning from me from future game jams (if Fred is banning me for being OP, I had to be doing something right), I started to think I was onto something with the central tension/victory point dilemma and this could be the key to my July Crisis game. Albeit not in the context of a negotiation, but maybe more in the context of a kind of projection of a state’s prestige. Instead of tension rising too high that it would cause an opponent to leave the negotiating table (causing you to lose if you made this happen), if tension rose too high you would cause an opponent to mobilize (causing you to lose for making World War I start).

But how to model a game of chicken as more than just a single event? Maybe make it a series of mini-games of chicken, with points awarded for each result? Maybe six? That would roughly correspond with each of the weeks of the crisis.

I thought of Pontoon/Twenty-One, and how that entices you to keep drawing cards to win to get the highest numbers, but there’s a risk you go bust and so lose. I started conceiving of the game as being essentially a card game, rather than being card-driven. Everything would hinge on the cards and how you used them, with everything else being tracks or ways to record scores.

But whereas Peace 1905 gave players access to all their cards from the beginning of the game, it felt as if managing your deck as you tried to form a tableau was a way to represent the kind of corralling that the key actors performed as they tried to juggle cabinets and government personalities of varying opinions into a coherent view. I didn’t know it when I started to think these thoughts, but I’ve subsequently wondered if Battle Line, and Condottiere in particular, had some part to play in this thinking.

In particular, in Condottiere you’re attempting to marshall a hand together while thinking about the danger of over-exerting yourself in the current phase so someone has an easier task of beating you in the subsequent one. In any case, Churchill blended in with the design again as I thought about personalities being your resource, but also your limitation.

These cards could also function as the cards in Pontoon/Twenty-One, where you can’t be certain you will get the number you want at exactly the time you want it. Isn’t the nature of a hand-management/tableau builder a fitting metaphor for trying to corral disparate personalities and agendas into a coherent policy that must sit within the context of the other (troubled and fragmented) policy projections of competing states?

Thus, a mere 40 years after I first started thinking about it, I not only had two ideas of what I wanted Crisis: 1914 not to be, but I also had an actual and clear idea of what I wanted Crisis: 1914 *to* be—and where I was actually trying to go with it.

Reaching the clear idea

So then, reader, I made it. (The details of this development once I had a really clear idea of what I was attempting to do are largely another topic.) And, since this path acquired a clear destination, it can finally be said more definitively to have been a journey.

Crisis: 1914 being playtested at Circle DC, April 2023. (Yes, that is Dan Bullock on the right.)

The moral of this particular story—no disrespect intended to the other designers referenced in this article—appears to be vermicomposting. That is, play, absorb, keep churning through ideas, and cycle through that for many years.Keep on going, and you will end up with something. If nothing else, it will be a direction of where you think you are trying to go.

Early board prototype for Crisis: 1914, winter 2022, by Sydney Stojkovic.

Board for Crisis: 1914 by Sean Cooke at Worthington Publishing, July 2023.

Crisis: 1914 is on Kickstarter through Friday, July 28. Maurice Suckling can be contacted on Twitter at @WriteGameRead.

References

Kermode, Frank. 2000. The Sense of An Ending: Studies In The Theory of Fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.