This post is from Mark S. Miklos, designer of GMT’s award-winning Battles of the American Revolutions (BoAR) series. That series, now in its 25th year, currently has 10 published volumes featuring 12 battles and 28 scenarios. Below, as part of a COI “My Favorite Card” series, Miklos talks about cards’ place in that series, and about one particularly notable card from Volume IV, Savannah. Stay tuned to COI Online for more designers’ “My Favorite Card” pieces in the months ahead!

“Allies Quarrel at the Battle of Savannah”

A Random Event Card in the Battles of the American Revolution Series by GMT Games

By Mark S. Miklos

The Battles of the American Revolution (BoAR) series is not a card-driven game system. The series was launched in 1998 and now includes ten volumes featuring12 battles and 29 scenarios. Cards are not used in the majority of these game opportunities.

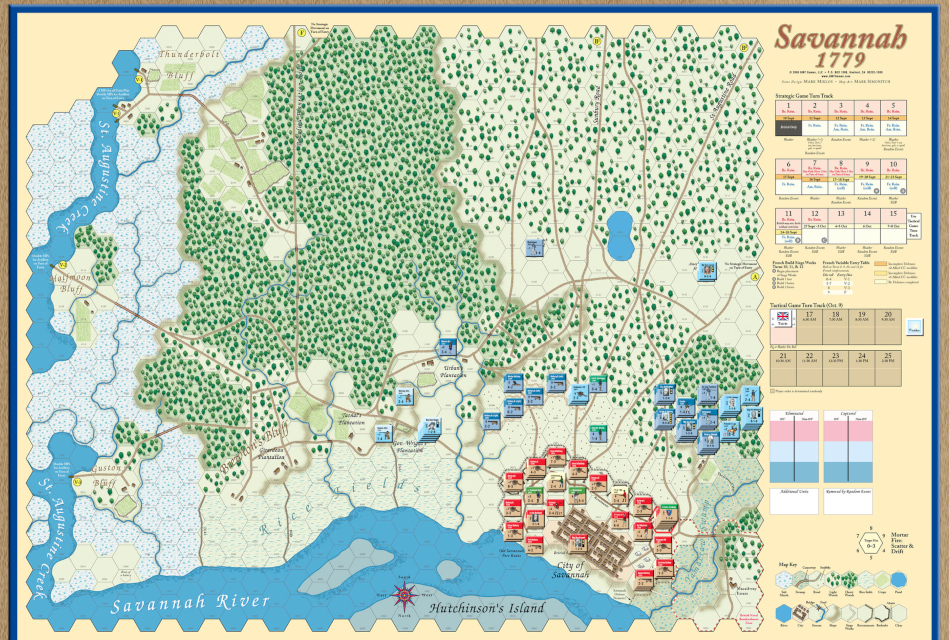

The cover for “Savannah.” (BoardGameGeek.)

Two of the games in the series, however, Savannah and Pensacola, model a siege followed by an assault. They cover weeks rather than merely hours on a single day. To leaven that experience, enrich the narrative, and offer a tableau of historical flavor, a single deck of Random Event cards was innovated for volume IV in the series, Savannah. These proved to be so appropriate that volume VII, Pensacola, also adopted its own version of a Random Event deck.

The three most recent three games in the series, on the battles of Newtown, Rhode Island, and White Plains, offer “Opportunity” cards. These differ somewhat from Random Event cards in that each player has a dedicated deck, and every card drawn can be used to enhance one’s play or diminish the play of one’s opponent.

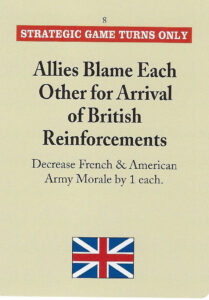

With this brief background to set the stage, let’s look at one card in particular; “Allies Blame Each Other for Arrival of British Reinforcements,” from Savannah, which gives a deeper insight into that design.

The Battle of Savannah in October 1779 was one of the most diverse battles ever fought in North America. Crown forces included British Regulars and Highland Scots, Hessian mercenaries, Loyalist American troops, Tory militia, Creek Indians, slaves commandeered from local plantations to help work on the defenses, and even civilian volunteers.

Arrayed against them was the combined Franco-American army. French forces included not only Metropolitan French regiments, but also regiments from France’s colonial possessions. Haitian militia augmented the force, as did a regiment of Irish volunteers fighting in the service of France against their English overlords. American troops included regulars and militia from the American Southern Army, as well as Count Casimir Pulaski’s famed and colorful Legion of European adventurers and expatriate British.

The back of the event deck for “Savannah.”

While not the first attempt by France to cooperate with its nascent American ally, (See Battles of the American Revolution Volume IX, Rhode Island), it was the first such attempt to consummate that alliance in action against a British occupying force. Major General Benjamin Lincoln was in command of the American army and in nominal overall command of the Expeditionary Forces, while the French were led by the mercurial and pedantic Admiral/General Comte d’Estaing. Of d’Estaing, a French soldier at Savannah would later remark, “He conducted himself as a brave grenadier but a poor general in the affair.”

Not only was Savannah second only to Bunker Hill as the bloodiest battle of the war in terms of casualties as a percentage of the troops engaged, the British victory there also had far-reaching strategic consequences. It ushered in the British Southern Strategy to break the stalemate of war in the northern theater, which was followed in turn by General Nathanael Greene’s reconquest of the South.

The composition of the protagonists, the fact that it was the first cooperative action between the French and Americans, the sanguine nature of the fighting, the personalities involved, and the long-term consequences of the campaign were all contributing factors that led me to design this volume in the series. Perhaps what inspired me the most, however, as I learned more about the Savannah campaign, and what convinced me that it would be an ideal candidate for a three-player game, was the nature of the Franco-American alliance and how discord between the Allies played out in disastrous ways on the battlefield. Modeling those nuances became my challenge. It has been said that allies are their own worst enemies. Seldom has that been more apparent then during the Battle of Savannah.

As events would prove, there was not only a latent mistrust between the French and the Americans, there was also discord within the French army’s hierarchy and that of the French navy. On the sixteenth of September, leading elements of both armies arrived on the field. Not waiting for the arrival of General Lincoln, d’Estaing instead opened unilateral negotiations with the British, inviting them to surrender “To the arms of the King of France.” Although France had the superior army, they were the junior partner in the alliance, and protocol would have dictated that the surrender be offered to Congress or at the very least to the combined arms of the besieging forces.

The British garrison commander, General Augustine Prévost, took the offer under advisement as a delaying tactic in order to improve his defenses and await the arrival of additional reinforcements known to be near. The ruse de guerre worked. On the very next day, coincidental with the arrival of General Lincoln, some 800 Hessian Grenadiers, Highlanders, and North Carolina Loyalist troops arrived in the city. Now fully garrisoned, Prévost rejected the offer to surrender.

The “Allies Blame Each Other” card from “Savannah.”

This incident transfers directly to the card we are describing in the essay today. The Allies immediately set about blaming each other for the arrival of the British reinforcements.

In game terms, the card requires both the French and the American player to each surrender one point of Army Morale. Upon seeing the arrival of the British reinforcements, Comte d’Estaing said, “I have had the mortification of seeing the troops of the Beaufort garrison pass under my eyes. General Lincoln, who could and should have prevented this, saw it and fell asleep in an arm chair.”

The Americans were to have blocked the land route from Beaufort, SC to Savannah, Georgia, while the French were to have blocked the sea lanes. Neither seemed to be aware of the intracoastal network of tidal creeks which, when led by local African-American fishermen, the British were able to use to transit their reinforcements.

Once it became generally known in the two armies that the British reinforcements had arrived, the rank and file soldiers began to blame each other. The French dismissed the Americans as insurgents and amateurs without discipline. The Americans accused the French of being haughty and overbearing. Thus, even before the joint venture against the British had properly begun, the two allied armies were clashing over politics and protocol and trading blame over military failures. This was not a good way to begin a martial contest against a determined and fortified enemy.

More mishaps were to follow. Those included entrenching tools promised by the Americans which did not materialize, drunk French mortar crews firing short rounds that landed among American troops, and discord between the French army and navy officers. On the night before the attack, d’Estaing completely scrambled his army’s organization. As a result, troops marched and fought under officers they did not know and alongside men with whom they had not trained. The target of the assault was also switched at the last minute from the British lines directly opposite the French siege approaches to the far right of the British line.

Jean Baptiste Charles Henri Hector, comte d’Estaing, seen in a 1769 portrait by Jean-Baptiste Le Brun. (Wikipedia.)

As a result, the French muster alone took an agonizing four hours and was not completed until 4 a.m. Whether by design or by accident, American guides who were supposed to lead the French columns to their starting positions were not helpful; more often then not, they led the French astray.

Meanwhile, the Americans were in their jumping-off stations at 1 a.m. and had to stand to their arms in the pre-dawn cold and dark and wait. The attack was to have been a surprise launched in darkness. Yet, by 5:30 a.m. with dawn approaching, only the French Avante Guard had reached its position. The rest of the columns strung out for miles.

At the far end of the battlefield where the Haitian militia was to launch a feint, the sound of firing could be heard as daylight broke and the battle was underway. Rather than five attacking columns charging together with bayonets in darkness, what actually happened was a series of confused and piecemeal attacks that allowed the British to concentrate against each attack in detail.

The results were a disaster for the attacking Allied forces. Comte d’Estaing was himself wounded twice and carried off the field. Count Pulaski was killed. His last words were “Follow my lancers!,” as that group was just then trying to clear a causeway to gain the right rear of the Spring Hill Redoubt. Colonel John Laurens, whose light troops three times stormed the Spring Hill Redoubt, gained the parapet, and were thrown back in fierce hand-to-hand fighting, looked back at the casualties among his corps that now littered the field, and exclaimed, “Poor fellows, I envy you.”

When the battle was over, with hurricane season in full swing, d’Estaing reembarked his troops and sailed for the Caribbean to protect the sugar islands. American militia began to desert in droves, and the American Southern Army limped back to Charleston.

David K. Wilson, in his book The Southern Strategy, summed up the campaign this way. “This incident is yet another example of the lack of cooperation and respect within the Expeditionary force. This disharmony existed not only between d’Estaing and his officers, but also between the French army and navy, between the regulars and the militia, and between the French and Americans. In light of this friction, it is not surprising that the expedition met with disaster.”

Benjamin Lincoln, painted by Charles Wilson Peale in 1784. (Wikipedia.)

There are many design elements in three-player Savannah that put players in the shoes of d’Estaing and Lincoln specifically. First, only a single player can win the game. As a result, even though the Allies have a common enemy to defeat, only one of them can “win” the game, assuming the British are defeated. This immediately sets up a friction between the Allies when it comes to utilizing shared resources.

Initiative for the Allies is tied to French Army Morale. While the French army is larger and of better quality, it is also more brittle as a result of the impact of card play. Thus, its Army Morale is more tenuous. And yet, it is that morale to which the Allied players link their single initiative die roll each game turn. To clarify, the Allies play together during a single Allied phase, even though they are two distinct players.

French and American units may not stack during movement or cooperate during combat. The one exception is Count Pulaski, who may stack freely. Further more, Metropolitan French regiments can’t stack with the Haitian militia. On the British side, Southern American Loyalist regiments may never stack with the African-American troops.

In every combat phase in the BoAR system, each side gets to use a single Diversion. There, to avoid a soak-off attack, they may exempt one enemy hex from being attacked by paying a negative column shift against the neighboring attack. In Savannah, this means the Allies get one Diversion per combat phase; not one each. Who gets it if each could benefit by using it?

The BoAR system uses a concept called Momentum. Momentum is represented by a chit: (five total are included in the game. Typically one side or the other starts a game with Momentum. In Savannah, the Allies get it.

Momentum can be earned though decisive combat results or in some cases through leader casualties. Momentum can be spent to influence the initiative die roll, to purchase additional Random Event cards, or to re-roll adverse close combat die rolls. Once again, if the Allies have one Momentum chit but each player could use it, who gets it? How is that decided?

Even the Random Event cards themselves pose a potential problem. Each card has a flag or flags shown on the button to indicate which player is entitled to play that card. On the sample card selected for this essay, only the British player is entitled to play it, by virtue of the Union Jack shown on the card. If a card were to feature both an American and French flag, only the French OR the American player may play it.

An important caveat there is that the Allies hold a single hand of cards; they don’t each hold a hand of cards. So if both players could utilize the benefit of a given card, but only one of them may do so, who decides?

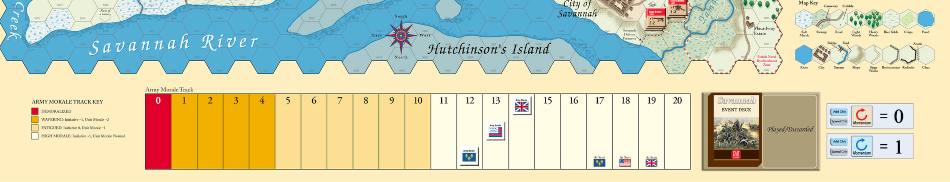

Even Army Morale becomes a factor. While each army tracks its own morale separately on the Army Morale Table, the British player need only reduce one of his enemies’ Army Morale to zero (demoralized) to win the game substantially. I already mentioned that the French morale is tied to Allied Initiative, and that the French morale is the more brittle between the Allies.

The Morale Track for “Savannah,” as seen at setup of the historical scenario. (GMT Games, via VASSAL.)

The rules for sharing all these resources (cards, diversion, and momentum) are intentionally open-ended. There is no proscriptive formula to determine precedence, and any agreement the players can reach that doesn’t violate the core series rules is permitted. As is the case in most diplomacy-based games, agreements are non-binding and may be broken.

It must be admitted that when playing with friends over the kitchen table some Saturday afternoon, these nuances of Franco-American friction may matter less. Everyone is in it for fun, and who finished first between the Allies may not matter so much.

Everything changes, however, in tournament play. The BoAR system has been a staple “Century” event at the World Boardgaming Championships (WBC) for more than 20 years. The games are played at RevCon at Prezcon, and have also been played over the years at numerous smaller regional events.

When plaques, AREA ratings and bragging rights are concerned, it most definitely changes the chemistry at the table. Three-player Savannah played in a tournament setting is the game at its absolute best. It gives the players a clear insight into the challenges, frustrations, and limitations faced by the commanders at Savannah.

And, when all is said and done, the Random Event deck is one component in that unique mix of design elements. It adds flavor to the game, historicity to the experience, and helps players “feel” the friction that was emblematic of the actual event. And “Allies Blame Each Other for Arrival of British Reinforcements,” and its Army Morale loss for both the French and Americans, particularly illustrates that.

About the author:

Mark Miklos, a first-generation American of Slovak descent, is the designer of GMT Games’s award-winning Battles of the American Revolutions (BoAR) series. Launched in 1998 with the Battle of Saratoga, the series is now in its 25th year and going strong. To date, there are 10 volumes featuring 12 battles and 28 scenarios. BoAR games have been played competitively at the Word Boardgame Championships (WBC) for 22 years. They are also the centerpiece of the all-Rev-War tournament “RevCon,” held annually at Prezcon. BoAR games have a wide and diverse following of both national and international players.

Mark graduated with a degree in history from the University of South Carolina, is honorably discharged from the USNR, and is a Certified Professional in Food Safety. He has taught history, owned a tour and transportation company in historic Charleston, S.C., been operations manager for a small manufacturing company, and the fencing coach at The Citadel and at Vassar College. He has spent the past 27 years in restaurant operations, training, and food safety culminating as the Director of Food Safety and QA Programming at the National Restaurant Association. Today he is semi-retired and a partner in the firm, Active Food Safety, LLC.

Mark and his wife Darlene have been married for 32 years. They live in the Atlanta, GA area. They have two grown sons and one 20-month old granddaughter. They enjoy long distance trekking, canoeing and camping, travel in general and visiting wineries, and watching their beloved Gamecocks and Yankees, in person when possible.

The system does not disappoint. I had the pleasure of watching the PrezCon final round 2023. As mentioned, the three-player Savannah is the absolute best.