This article is from Edgar Milik, a long time board and historical gamer and technological facilitator for SDHist. It is based on the 2016 Terraforming Mars board game, designed by Jacob Fryxelius and published by FryxGames, Stronghold Games, and more, plus its Prelude expansion.

Terraforming Mars (2016) is a popular board game where players over many generations convert Mars into a human livable planet. The game, like the mythical Cassandra who is cursed to warn others about the future but always be misunderstood, is commonly discussed as a celebration of science, technology, and progress, despite portraying what may be a dark future for the majority of humanity. But Terraforming Mars‘ setting is a place where unchecked oligarchs bombard the planet from space at their whims, where workers have no voice in their own lives, and where the players rule in a world with little legal restraints on their power.

This model of the future starts before the game begins with the selection of player factions. Despite nominally representing corporations, the players at no point worry about their company’s profits or the presumed shareholders’ concerns. The players are better described as abstracted billionaire CEOs who wield their company budgets as personal expense accounts for anything they wish, with the game’s victory points most closely tied to an abstraction of celebrity prestige of the CEO.

In particular, it’s worth noting that while the game cannot end until Mars is terraformed, the winner of the game does not have to do any of that terraforming. They can instead spend their entire time scoring other sorts of points, such as breeding animals or building spaceships. The actual terraforming is incidental though often useful, but celebrity appears to be the real currency of this future.

The game implies that nation-states are no longer a thing, replaced by a united World Government. Despite presumably representing the entirety of the human population, that government is not particularly powerful or noteworthy to gameplay. The government’s combined terraforming efforts, representing all the public sectors of the entire planet, are available as one player faction called the United Nations Mars Initiative. Its unique player power is to convert money into points (notably, not a terraforming effect, just points).

Some cards from the physical version of “Terraforming Mars.” (Andrew Bucholtz photo.)

The future Earth-wide government has no further direct impact on gameplay, other than as the presumed court system that settles the dispute in the card “Mining Rights,” and possibly being the entity receiving the money on “Bribed Committee”.

The cards have a mixed message on the ethics of the future. While “Hackers,” which steals money from another player, costs the person playing it a victory point, the similar “Hired Raiders” and “Sabotage” cards have no downsides. White collar crime is also winked at: starting a “Cartel” is also pure profit and the “Allied Bank” is cheekily described as a way for “Putting peoples’ savings to good use”.

It’s not immediately clear why “Hackers” is enough bad publicity to warrant an actual penalty while sabotage, raiding, and corporate crime are not. Possibly the future of Terraforming Mars has a special taboo for computer fraud and abuse.

While the Earth is explicitly referred to on many cards, it’s not particularly important to the players. The old world can be converted into money (“Business Empire,” “Eccentric Sponsor,” “Allied Bank,”) or into projects (“Invention Contest,” “Business Contacts,” “Business Network”), and that’s basically its only usage.

The opinion of people represented through the World Government do not matter other than as the judges of this race for fame. And their wills do not act as a limitation on the players.

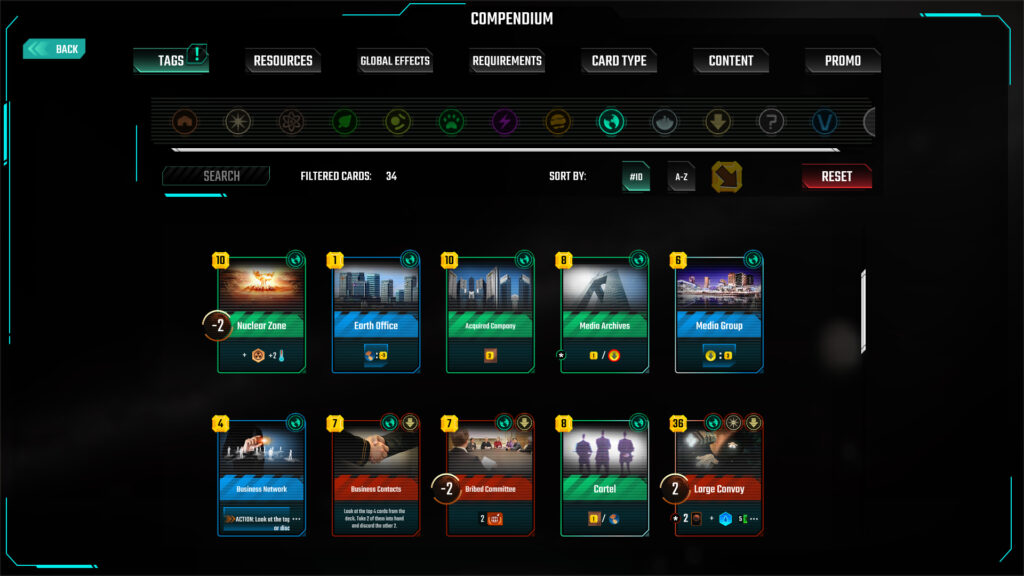

Some of the Earth cards from “Terraforming Mars.”

One real world government agency does make a special appearance by name, though: NASA pops up as WASA. In-game, it has been privatized and sold off to a player who gets access to its store of titanium and two project ideas. The historical public sector space exploration programs have no other game effects.

While we’re told that there exists a World Government on Earth, it’s also apparent that no such governing body can form on Mars. And that’s no matter how many in-game centuries pass or how many people live there.

Instead, the citizens of Mars arrive as either “Indentured Workers,” who offer big financial savings to the players at the cost of some bad publicity, as transplants (“Immigration Shuttles” and “Immigrant City”), who are represented in game as small fluctuations to the corporation’s income, or as prisoners (“Callisto Penal Mines”) with a flavor quote explicit enough to make Michel Foucault blush: “You always wanted to be a warden, didn’t you?”

These new Martians have no impact on gameplay at all, other than as prestige for the players who own the cities they live in. While the modeled humans of Mars never attempt to influence their lot, the game does have some cards that would be helpful in stopping them if they tried.

That includes “Robotic Workforce,” which is presented as “Enhancing your production capacity,” but would make for an effective countermeasure to a labor movement. There’s also a company town, “Corporate Stronghold,” to guarantee greater control over the workers’ autonomy. And in the case it all starts going wrong, there’s a “Security Fleet” with the slightly ominous flavor text of “Keeping the peace by force.”

Edgar Milik. Photo by Angelica Milik.

‘Keeping the peace’ might be a reasonable concern for the players, as future Martians might have some very good cause for united resistance. After all, a common method for terraforming is simply dropping colossal rocks (“Huge Asteroid,” “Metal-Rich Asteroid,” “Giant Ice Asteroid,” “Nitrogen-Rich Asteroid,” “Asteroid”), comets (“Comet”, “Towing a Comet”), or entire moons (“Deimos Down”) on the planet.

The players can also cause “Flooding” to damage other players’ tiles, including populated cities, or just nuke the planet by creating a “Nuclear Zone.” (That last one does come with a small points penalty, presumably from some bad publicity.)

The flavor text of the card “Society Support” is of particular interest. Since there is no Mars government that could help provide for the people living there, everything has to come from the players through cards like this one. Its flavor text says “Meeting the needs of society is good, because it’s your society.” While that “your” can be read as a statement of participation, our theoretical Cassandra might have also meant it as a warning about complete corporate ownership of this new world.

It’s possible that Terraforming Mars (2016) may be destined to join the ranks of other sci-fi works which portrayed dystopias, whose warnings morphed into guidebooks for up-and-coming Silicon Valley startups. Fingers crossed Apollo’s gift of prophecy missed in this case.

Edgar Milik has been pushing counters on hexes since running across the Polish edition of Gondor (“Bitwa na polach Pelennoru”) back in the 80s. He’s now involved with both SDHist and the Zenobia Award in a technology advisement role, and occasionally somehow finds time and table space to still run an occasional board game.

Digital screenshots here are from the Twin Sails Interactive Steam version of “Terraforming Mars.” Physical game photos are from editor Andrew Bucholtz.