This piece is from SD HistCon founder Harold Buchanan. This is the second piece in a six-part series looking at the history of San Diego in World War II. (The first part can be read here. If you’re interested in registering for SDHistCon Summit 2023 from Nov. 3-5 and exploring some local history along the way, limited tickets are still available here.)

In part two of the discussion of the impact of World War II on San Diego, we cover the San Diego Tuna Fleet and its transition into wartime demands. Expect a new post in this series each Monday for the next four weeks. Harold is an award-winning designer whose designs include Liberty or Death (2016), Campaigns of 1777 (2019), and Flashpoint: South China Sea (2022). He has been a historical gamer since 1979. Harold is an Adjunct Professor of Finance at The University of California San Diego.

In the study of the United States’ participation in World War II, the incorporation of civilian maritime fleets for wartime efforts offers a compelling narrative of adaptability and resilience. Central to this narrative is the San Diego tuna fleet, which underwent a fascinating transformation in response to the exigencies of wartime demands.

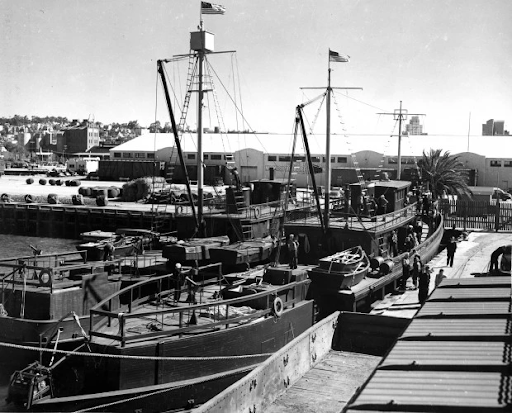

During the tumultuous years of the conflict, several vessels from the San Diego tuna fleet were requisitioned by the U.S. military establishment. Historically, the speed, maneuverability, and robustness of these vessels, specifically the tuna clippers, rendered them particularly apt for military appropriation.

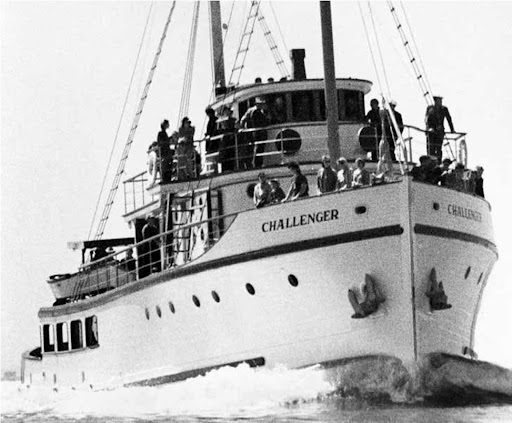

Upon requisition, a meticulous process of modifications ensued. These ranged from the installation of armaments—machine guns and depth charges for anti-submarine warfare—to advanced communication apparatus. Additionally, enhanced navigation systems, inclusive of nascent radar technology, were integrated. Protective measures, such as hull reinforcements, further augmented their battle readiness.

These reconfigured vessels assumed many different roles:

- These vessels were often utilized for coastal surveillance, a defense measure to forestall enemy encroachments close to U.S. maritime boundaries or critical naval passages.

- An auxiliary yet vital function was the identification and disarming of naval mines.

- Given their intrinsic speed, these vessels became instrumental in Pacific theater search and rescue operations.

- They also facilitated the movement of essential goods, personnel, and intelligence between naval bases and frontline regions.

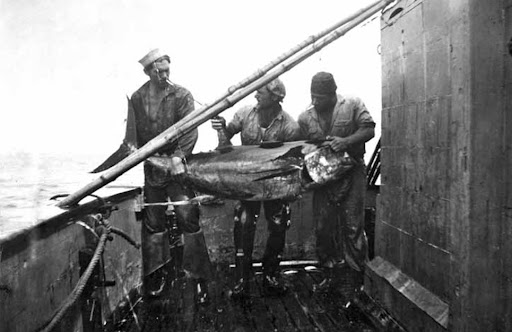

Intriguingly, many erstwhile fishermen were assimilated into the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard. They possessed a deep familiarity with the Pacific waters and their requisitioned vessels. And their maritime prowess, especially their knowledge of the Pacific topography, proved indispensable.

The war, however, imposed constraints on the tuna industry. Traditional fishing vicinities, especially those proximal to Pacific conflict zones, metamorphosed into perilous territories. Despite these impediments, the tuna industry pivoted to cater to the military’s sustenance needs, with canned tuna emerging as a dietary mainstay for servicemen.

The 49 tuna clippers taken by the Navy and three by the Army represented about 55 percent of the fish-carrying capacity of the entire bait boat fleet.

On February 25, a fleet of 16 tuna clippers, painted gray and marked with YP number designations as Yard Patrol vessels, left San Diego harbor for picket duty to protect the Panama Canal.

In May 1942, a convoy of six YP Clippers left San Diego for Hawaii. These YPs transported supplies to French Frigate Shoals and the islands of Midway, Johnston, Fanning, Christmas, Palmyra, and Canton. In June 1942, seven YP Clippers left San Diego for service at Efate Island, or Samoa, or Auckland, New Zealand.

In November 1942, another group of five headed for the U.S. Naval base at Tutuilla, Samoa. As the conflict moved towards Japan, YP Tuna Clippers were sent on missions to other Islands and Atolls of the Western Pacific.

During the Solomon Island Campaign in 1942, the Paramount (YP 289) and the Picoroto (YP 290) delivered frozen turkeys and all the fixings for a traditional holiday feast at Guadalcanal Island. In 1943, frozen turkeys were also delivered to the Marines fighting on Bougainville in time for Thanksgiving by the American Beauty (YP-514).

Two “Yippies” (YP numbers) were sunk in the Solomon Islands campaign by enemy surface ships. On Sept. 9, 1942, off Tulagi Island, the Prospect (YP-346) was sunk. And on Oct. 25, 1942 off Guadalcanal Island, the Endeavor (YP-284) was lost.

Two YPs were lost in the Midway region. On 23 May 1942, the Triunfo (YP 277) was destroyed

Tuna Fleet Service, World War II (1941-1945) by fire and explosions en route to French Frigate Shoals (North of Hawaii), and then scuttled to avoid enemy capture. During October 1942, the Yankee (YP-345), with a 17 member crew, on a voyage from Pearl Harbor to Midway Island via French Frigate Shoals was “lost without trace from causes unknown”.

The successful wartime experience of the “Yippies” caused the Navy to build 30 wood-hull vessels patterned on the Tuna Clipper design. Each of the 30 newly constructed Navy YPs was 128 feet in length, of 14 feet draft, and powered with a 500 horsepower diesel main engine. They were built during 1945.

Subsequent to the cessation of hostilities, a phase of reversion and reconstruction dawned. While some vessels were retrofitted to their original configurations, others retained their wartime modifications.

The post-war era was not devoid of challenges for the tuna industry, marked by competition and fluctuating tuna populations. That led to the gradual eclipse of San Diego’s primacy in tuna fishing in the subsequent decades.

The metamorphosis of the San Diego tuna fleet serves as an emblematic representation of civilian industries’ wartime mobilizations. Its history during World War II underscores the profound intersections between civilian enterprise and military strategy during one of the most critical epochs in American history.

You can follow Harold on Twitter here.