This post is from Dr. Stuart Ellis-Gorman. Here, Dr. Ellis-Gorman describes the progress of the We Intend To Move On Your Works project of playing through and discussing American Civil War games that he and Pierre Vagneur-Jones have been conducting, which comes with a particular focus of looking at the intersection of the Lost Cause movement and wargaming. See also their interview with SDHist’s Andrew Bucholtz at SDHist Second Front 2024:

Background

It is a matter of general agreement that the first modern hobby historical wargame was Gettysburg, designed by Charles S. Roberts and published by Avalon Hill Games in 1958. In 1961, Avalon Hill followed up Gettysburg with Chancellorsville and Civil War, both designed by Charles S. Roberts, and in 1962 Gettysburg was republished with substantially revised rules, including a change from squares to hexes on the game map. While this was hardly the exclusive output of historical wargames from Avalon Hill during this period (U-Boat was released in 1958 and the influential D-Day was released in 1961), it is safe to say that American Civil War games were a crucial part of the foundation of the board wargaming hobby from its very inception.

The 1964 box of “Gettysburg,” designed by Charles S. Roberts. (Photo via @Offa on BoardGameGeek.)

Perhaps that shouldn’t be all that surprising, though, because these games were not released in a vacuum. The early 1960s marked the centenary of the Civil War and was a time of very intense reflection and debate about the war and its legacy. This was also a high point in the American Civil Rights movement as black Americans fought for freedoms they had been denied in the postwar South (and elsewhere in America) despite the promises of Reconstruction. These two moments often intersected, such as the choice by many white Americans to use the Confederate battle flag of the Army of Northern Virginia as a symbol of opposition to equal rights for all Americans.

This intersection of the birth of historical wargaming with a cataclysm of America reckoning with its own past interests me. In particular, I’m curious about the effect that the Lost Cause may have had during the birth of the hobby and to what extent it has persisted. For those not familiar, the Lost Cause is a historical movement of sorts that pushes a revisionist Neo-Confederate narrative of the American Civil War. It was formed in the war’s immediate aftermath: the name comes from Edward A. Pollard’s book The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates published in 1866, and it emerged from the Reconstruction era as arguably the dominant narrative of the war.

The Lost Cause has had many narrators each with their own interpretations, but a few truths hold no matter who is telling the story. Key among these truths are that the American Civil War was not caused by slavery, rather it was an aggressive war instigated by the northern states; the Confederacy had far superior soldiers and was defeated only due to the greater industrial power and population of the northern states; and that generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, as well as President Jefferson Davis, were among the greatest Americans to ever live who fought steadfastly for the rights of Americans against an oppressive northern regime. There are other popular but not universal themes as well, such as the notion that slaves in the antebellum South were happy and that slavery was benign (denying the murder, exploitation, and sexual violence that defined the “peculiar institution”).

The Lost Cause succeeded far beyond its initial authors’ hopes and became a widely accepted narrative of the war and its aftermath. Lost Cause histories written in the early twentieth century won Pulitzer Prizes and have been read by millions of Americans. The narrative even crossed the oceans and no less a figure than Winston Churchill wrote a narrative of the American Civil War that was deeply sympathetic to the Lost Cause.

Perhaps no single success can compare to the Lost Cause’s impact on cinema. Birth of a Nation, one of the most influential films of all time, is pure Lost Cause revisionism, but it is Gone With the Wind, arguably the most profitable movie ever made, that represents the Lost Cause’s greatest success in terms of reaching a wide audience. The Lost Cause functioned as a religion in the postwar South, with the dead soldiers as martyrs and Lee often described as a Christ-like figure. This was serious stuff to millions of Americans, and taken as gospel (literally).

There has always been resistance to the Lost Cause narrative, W.E.B. DuBois’ description of Robert E. Lee written in the 1920s is one of the finest examples. And by the 1960s, these were beginning to gain ground. That did not stop Lost Cause elements from featuring prominently in many popular histories of the time, such as in novelist Shelby Foote’s frequent praise for noted slave trader and war criminal Nathan Bedford Forrest in his three-volume history of the war published between 1958 and 1974. But by the 1970s and 1980s, the tide was turning against the Lost Cause rather decisively.

While its prominence is greatly reduced, the Lost Cause is not gone. One need only pay the briefest attention to arguments over Confederate statues in America to see Lost Cause arguments crop up again and again. The true history is winning, but the war is still far from over.

What Am I Doing?

Sometime in 2022 I decided it would be interesting to write about the intersection of the Lost Cause and wargaming–looking at wargames on the American Civil War across the decades and considering them against the backdrop of historical knowledge that we have about the conflict. Elements of Lost Cause-ism would have been almost impossible for Charles S. Roberts to avoid when making his initial games–the narrative was so prevalent during that era–but I also wanted to know how long the tail of that was. To what extent has the Lost Cause survived within wargaming?

Before I could write anything, though, I had to do some research. I had only played a couple of games on Gettysburg at that point, hardly a firm basis for so far reaching a project. With that goal in mind, I drafted a poor, innocent Anglo-Frenchman named Pierre as my opponent and started a project eventually titled We Intend to Move on Your Works, a riff on Grant’s famous terms of unconditional surrender offered to the Confederates at Fort Donelson. This project would be an ongoing account of American Civil War games as we played them: our initial impressions and any themes we noticed as we went. The goal was (and remains) that I would write something more comprehensive once we finished playing a wide sample of games.

We started in January 2023, and as of writing we are about 18 months into the project. That makes this a good time to reflect on what I’ve found so far. These are still very tentative arguments, early findings based on progress so far and by no means intended as definitive. I’ve decided to highlight a few themes that have stood out to me across the games we have played, namely: Confederate Competence, Confederate Solitaire, Confederate Language, The Battle Flag, and Pure Wargames.

Confederate Competence

In the opening line of his General Order #9, delivered to his army during the surrender at Appomattox, Robert E. Lee wrote: “After four years of arduous service marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude, the Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources.” This sentiment, that he had been defeated by overwhelming numbers and resources, laid the foundation for a myth that has endured to this day. In his self-serving narrative of his own defeat, Lee discredited the notion that he had made any errors or that his enemies had any competencies of their own – the Confederacy was defeated by greater resources, not by skilled generals and determined soldiers.

Entire books have been written on how this simple lie was expanded into an extensive false narrative of the American Civil War which placed Lee among the greatest military generals to have ever lived and denigrated all those who fought against him as his inferiors. I don’t have time to fully rehash them now, although I would point interested parties to the entertaining popular history video series Checkmate Lincolnites for an excellent (and humorous) summary of the current scholarship.

Suffice to say that the Confederacy was defeated in the field of battle. The Union had an enormous challenge in terms of conquering and subjugating the Confederacy and while they had superior industrial power and a larger population that is by no means a guarantee of victory. From the American Revolution to the Vietnam War, history is filled with clear examples of vastly outnumbered and outgunned sides winning their wars, and the Confederacy had many advantages that the American colonists did not.

Compared with the British, the Union had to conquer an area far larger than the original thirteen colonies of the Revolutionary era against a virtually unified population, with no base of Loyalist supporters to assist them. Nevertheless, the belief in the superiority of the Confederacy in terms of purely military capability is perhaps the most prevalent Lost Cause legacy I’ve found so far in my examination of American Civil War games – and I haven’t even tackled the strategic level games where I expect it could be even more prevalent.

Sometimes this superiority can be baked into the game’s rules. The core rules for Great Campaigns of the American Civil War give the Confederates a +1 to all of their movement as well as combat bonuses for many key generals, like Lee and Jackson, who were also pillars of Lost Cause myth and religion.

Other times it shows up in games as a general superiority in the quality of the soldiers. Longstreet Attacks by Hermann Luttmann is an excellent game, but its unit cohesion stats (which represents more their morale than their numerical strength) show a far superior Army of Northern Virginia attacking a weak and often unreliable Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg. In doing so, it tacitly supports a notion that only the end of the day, not stiff Union resistance, caused the Confederate attack to fail on the 2nd of July.

“Longstreet Attacks,” by Hermann Luttmann. (@Handeman on BoardGameGeek.)

To an extent, design choices like this may reflect a desire for achieving game balance. But even if the result is unintentional, that does not mean that they cannot also be a remnant of Lost Cause-ism within the game’s design.

I’ve found anecdotally in feedback to my coverage of many games that the notion that the Confederacy was the superior fighting force has taken root in some parts of the wargaming hobby, and they push back on the fact that this is a Lost Cause falsehood. I am most curious to see how this is represented in more operational and strategic games. I’ve played mostly tactical games, and at a tactical level the strength of units usually reflects actual historical strength (although it must be noted that distorting of army strength was very common in post-war Lost Cause writing). However, at a higher level it is more common to see stats assigned to generals to reflect their capability. These are value judgements by the designers, and thus more susceptible to the influence of flawed and propagandist historical arguments.

Confederate Solitaire

There are a truly bizarre number of solitaire games where the player is tasked with taking on the Confederacy and winning either the war or a key battle in hopes of turning the tide of history.

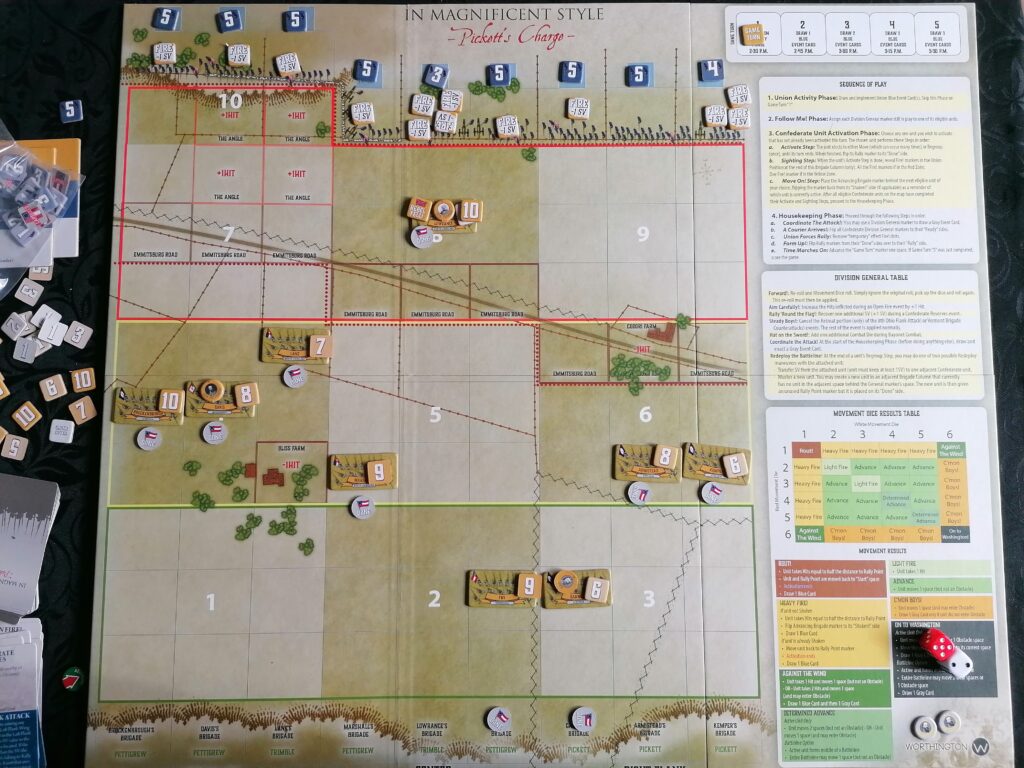

Three games ask you to win Pickett’s Charge or Gettysburg more generally for the Confederacy (In Magnificent Style by Hermann Luttmann, Gettysburg Solitaire by Sean Cooke, Mike Wylie, and Grant Wylie, Pickett’s Charge the Last Attack at Gettysburg by Michael W. Kennedy), two games ask you to win the whole war (Jeff Davis by Ben Madison and The Lost Cause by Hans von Stackhausen). Field Commander Robert E. Lee by Vincent Cooper gives you the chance to win several of Lee’s famous campaigns, Shiloh Solitaire (also by Michael W. Kennedy) asks you to defeat General Grant at the very start of his career, and Mosby’s Raiders by Eric Lee Smith lets you play the (in)famous scalawag during his Civil War raiding days. That is eight games where players represent the Confederacy. In contrast, I have found only two solitaire games, Confederate Rebellion by Dave Kershaw and Assault at Cold Harbor by Gary Graber, that put you in the shoes of the Union.

“In Magnificent Style,” designed by Hermann Luttmann. (Photo by Dr. Stuart Ellis-Gorman.)

Solitaire games carry an extra burden on their choice of the history they represent. In most conventional wargames you get multiple perspectives from the game – a minimum of two sides clashing against each other. In a solitaire game, only one side is given player agency, and so players are put in a position of being just that one side and experiencing their perspective.

It is harder to convey the alternative perspective. And by their very nature, humans are more likely to identify and sympathise with the side they are playing. It is effectively stacking the emotional deck, lending an automatic layer of sympathy with the game’s protagonists. This is why it is a little troubling that in solitaire games it is far more common for players to play as the Confederacy.

Pickett’s Charge has a prominent position in the narrative of the Lost Cause – it was the “high water mark” of the Confederacy, supposedly the moment they came closest to winning the war. William Faulkner, the famous Southern writer, eloquently described how significantly Pickett’s Charge lived on in the memories of Southerners in the generations after the war was over, it was almost a holy event, a glorious final charge for a dying institution (meaning the Confederacy, of course, they would never admit slavery’s centrality to the conflict).

Games like In Magnificent Style do not meaningfully engage with this legacy or offer any kind of analysis of it, and instead simply use Lost Cause wallpaper to decorate an otherwise engaging push-your-luck game. In Magnificent Style trades on the reputation of Pickett’s Charge, which is so famous precisely because of the Lost Cause, to sell more copies but does not want to do the work in terms of challenging the flaws in its narrative or even really examining what it is the game is asking you (the player) to fight for. Instead, it simply asks players to win one for Dixie, and by implied extension hopefully ensure the continued enslavement of Americans.

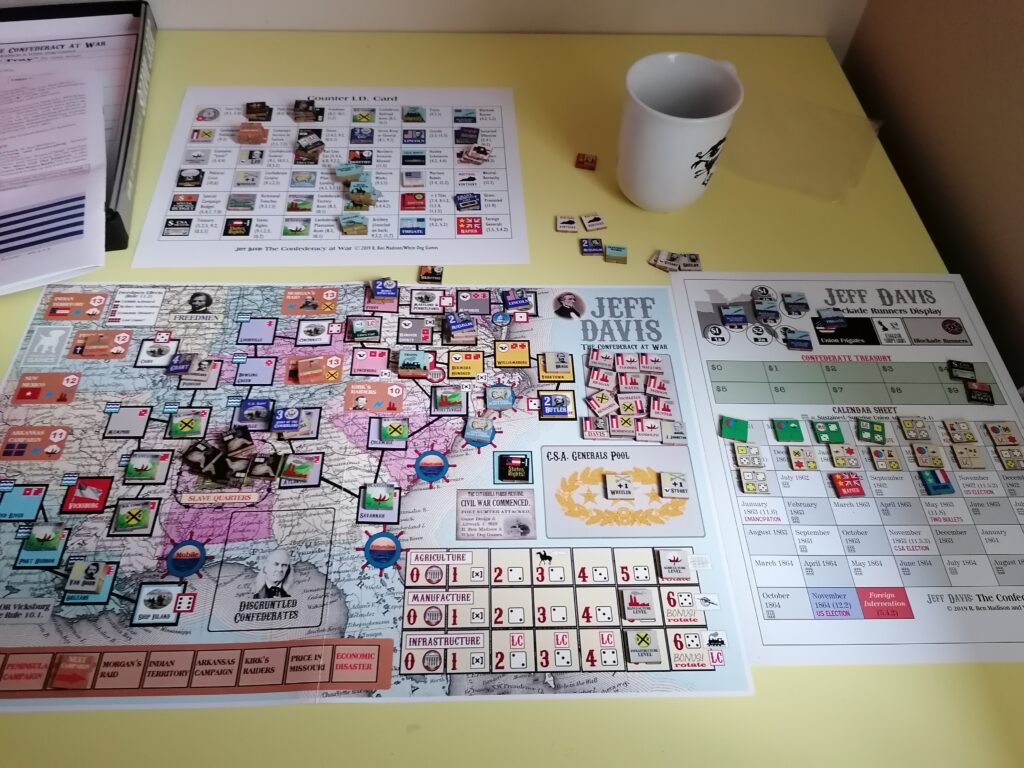

While Jeff Davis does at least include slavery in its mechanisms, and thus acknowledges something that very few American Civil War games will, the design fundamentally misunderstands how slavery and the slave economy worked. The designer notes also include frequent instances of strange Lost Cause takes–expressing a sympathy with the South despite admitting to its pro-slavery agenda and at one point trotting out the old lie that some slaves were “well treated” but ran away, nevertheless.

The result is a mess, a game that seems to accidentally endorse slavery, or at least separate but equal segregation, without seeming to be fully aware of what it is doing. Also, as a States of Siege style-game, it presents a Confederacy under attack and tacitly endorses a view of United States aggression against a South that simply wants to be “free.”

“Jeff Davis,” designed by R. Ben Madison. (Photo by Dr. Stuart Ellis-Gorman.)

I want to stress that I don’t believe a solitaire game where you play as the Confederacy is inherently off limits or necessarily an expression of Lost Cause sympathy. However, none of the games I have played have shown any serious engagement with the legacy of the Lost Cause or what the American Civil War was about. The closest was Jeff Davis, but its interpretations are so bizarre that they become their own form of troubling and problematic.

If you want to put your players in the shoes of slavers, you need to make it clear to them what they represent and what their actions mean, not simply paper over them and hope no one will notice. Proponents of the Lost Cause want the hard political truths to be forgotten so that the veneration of the veterans and generals can take center stage in the memory of the war. They want you to think Robert E. Lee and George Pickett, not slave whippings and institutionalised rape.

Confederate Language

From its very inception, the nature and name of the American Civil War was in dispute. The government of the United States maintained that the Confederacy was a rebellion, and thus preferred the name War of the Rebellion. In contrast, the Confederacy believed that they had dissolved the Union and were thus a separate and independent nation–one that the United States invaded, thus initiating the war.

The Confederacy preferred alternative names, like War Between the States, War of Northern Aggression, or the somewhat tongue-in-cheek The Late Unpleasantness. The title American Civil War was the Union’s choice, but it represented a softening of their initial stance by abandoning the previous Rebellion title. While the name Civil War has remained the most popular, in Lost Cause circles it is tantamount to heresy to use it over one of the more Confederate-friendly names.

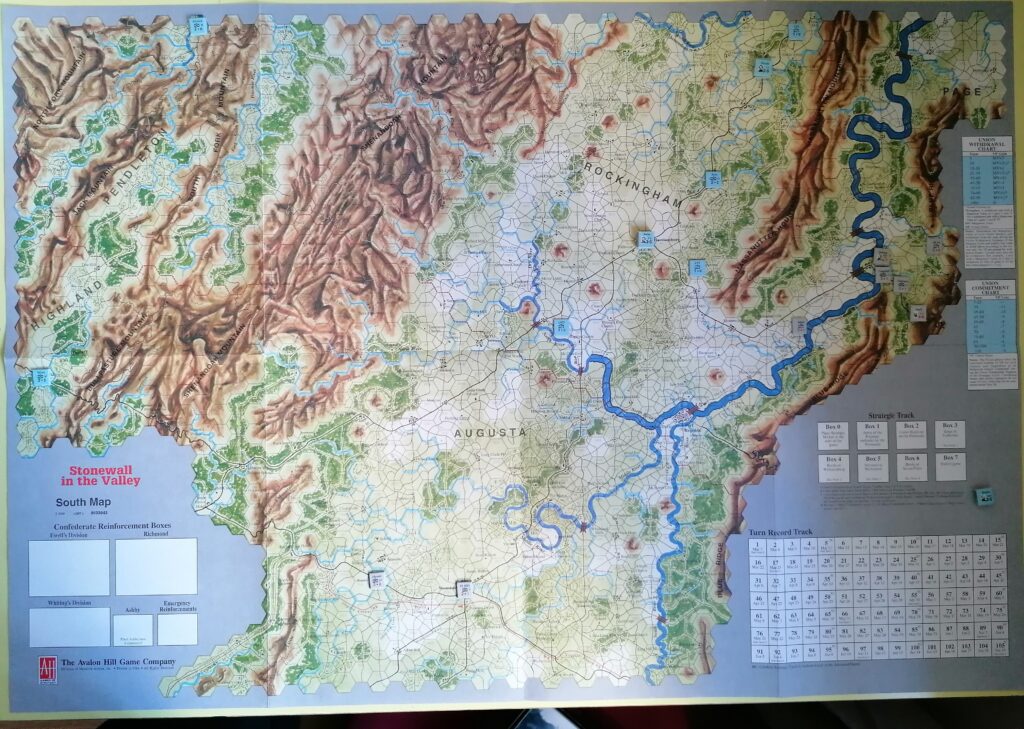

There are several games that use the literal Confederate name for the war, such as Ira B. Hardy’s War Between the States (1977) and Alan Emrich and Frank Chadwick’s A House Divided: The War Between the States 1861-1865 (1981). Steve Ruwe titled his operational game The Late Unpleasantness (2019), a milder but still Southern-leaning name. So far, I’ve yet to find a game that has fully committed to the label War of Northern Aggression (thankfully), while there is at least one game called Confederate Rebellion. Other games use quotes from famous Confederate generals, such as Hermann Luttmann’s A Most Fearful Sacrifice, or take the names of famous generals. Three games in the storied Great Campaigns of the American Civil War have “Stonewall” in their title.

“Stonewall in the Valley,” designed by Joseph M. Balkoski and part of the Great Campaigns of the American Civil War series. (Photo by Dr. Stuart Ellis-Gorman.)

The use of these titles are not indications that the people behind them were Confederate flag-waving rebels. Naming a game is difficult and there is certainly a desire to not just name every game “The Civil War” or “Gettysburg”. If you want your game to stand out, you need to use a name that people will remember. However, names are also not entirely neutral, and choices have consequences, even unintended ones.

Consider the game Last Chance for Victory, a tactical Gettysburg game by Dean Essig and part of MMP’s Line of Battle series. One popular narrative of the American Civil War places Gettysburg as the turning point in the war–after Lee’s defeat there it was all downhill and defeat was inevitable. Many people will be familiar with this idea, and maybe even the phrase “high tide of the Confederacy”. What they may not know is that this has a surprisingly strong connection to the Lost Cause.

When looking for explanations for how they lost, post-war Confederates (most especially General Jubal Early) eventually settled on Gettysburg as a useful explanation. It was Lee’s greatest defeat, and they set about first pinning the blame for it on men other than Lee (Longstreet was a popular scapegoat due to his post-war conversion to the Republican party) and to avoid giving any credit to Grant and his campaigns of 1864.

The truth is that Gettysburg is nearer the war’s mid-point than its end. The war would last for nearly two more years from July 1863 until April 1865. The Confederacy had an excellent chance of winning in 1864 had Lincoln lost his re-election (a close-run thing, possibly only successful thanks to Sherman’s capture of Atlanta in September 1864). Gettysburg was anything but the Confederacy’s last chance of winning the war, but a game about Gettysburg titled Last Chance for Victory certainly suggests that it was. It may be a catchy title, but it also states a Lost Cause myth in plain English, whether intentionally or not.

The Battle Flag

The Confederate Flag, both the actual one and the battle flag that people often mean when they say Confederate Flag, are symbols of White Supremacy. They were created for and used by a rebellion whose primary purpose was the enslavement of their fellow humans based on the color of their skin. After the war they served to commemorate that cause, as well as that of the so-called “Redeemers” who reinstated white supremacist rule during and after Reconstruction. In the mid-20th century, they were used as prominent symbols of opposition to desegregation and attempts to establish equality in America.

Waving of these flags was not merely bad manners. People were beaten, tortured, and killed in the name of the white supremacy that these flags represented. The “Heritage not Hate” movement, which has tried to brush this history under the rug and claim that these symbols are simply the past with no political baggage should not be taken seriously–they are denying the actual history in favor of the symbols of a white supremacist rebellion that killed hundreds of thousands of Americans.

Given the flag’s white supremacist meaning, designers, artists, and publishers should think long and hard about including it in their game. This history is not long dead–people who are still alive today were assaulted, beaten, and had family members killed by people waving the flag. The expected justification for why you would use a Confederate flag in your game is, of course, that it is historically accurate–these are the symbols the Confederacy used and it would be incorrect to use anything else.

The battle flag is used very casually in American Civil War games, and often in places where it is not even appropriate. Take a game like Into the Woods, designed by Dick Whitaker and published by GMT Games–as of writing the most recent entry into the venerable Great Battles of the American Civil War series. This game uses battle flags on several of its counters despite being about the Battle of Shiloh–at that battle the Army of Tennessee did not use the battle flag pattern, and in fact the Army of Tennessee was the most resistant to adopting the St. Andrew’s cross pattern into their army flags even later in the war when it became more common across the Confederate army.

This is the incorrect symbol to use for this army and this battle, and is a symbol of white supremacy, so why use it? I don’t think it’s because anyone involved in making it is advocating for white supremacy, but I do think they have not thought through the implications of casually using this symbol in the game. The Lost Cause’s campaign to normalize symbols of the Confederacy has made many (mostly white) people view this as a symbol just like any other rather than fully taking on board exactly what it means and who it supports.

I mention Into the Woods because it is a good example of the continued presence of this symbol in games, not to single it out as the only example. Many games use the battle flag symbol. Even the new map designed by Terry Leeds for Mark Herman’s For the People uses it rather than any of the more appropriate flags of the actual Confederacy.

The new mounted map for “For The People,” designed by Mark Herman. (Photo by Andrew Bucholtz.)

This symbol is used casually, often by people who were exempt by their birth from its ugly history, and it warrants further thought. Designers, artists, and publishers should think more carefully before printing white supremacist hate symbols in their games.

Pure Wargames

Hex and counter wargames dominate the market for American Civil War gaming. The majority of the games I have played for this project have been hex and counter ,and most of the games I still have yet to play are hex and counter as well. Even more than that, these games include little to nothing in the way of rules or systems to incorporate the political side of the war that was so crucial to determining its outcome.

While an excuse can be made that it wouldn’t be practical to include politics in a tactical level wargame, the same cannot be said of some of the operational and strategic wargames that similarly neglect this area. While there are notable exceptions (such as Mark Herman’s For the People, a card-driven strategic level game that includes many historical events in its deck of cards and factors many political considerations into its design), they are very much in the minority.

That individual tactical games do not include politics is understandable, and I have no inherent objection to that. However, the predominance of tactical games about the American Civil War, especially when combined with the fact that most operational games also neglect the political side of the war, is where I have some concerns. Essentially, it seems very clear to me that designers of American Civil War games do not want to factor politics into their decisions–they want to focus purely on the kinetic warfare: the battles, the campaigns, the movement of troops and the weaponry they carried.

Grand Havoc: Perryville, designed by Jeff Grossman. (Photo by Dr. Stuart Ellis-Gorman.)

This in and of itself isn’t Lost Cause-ism. I would actually align it more with the Reconciliationist stance of the post-war period.

To abridge a very complex topic, after the war ended three major movements formed to debate how best to reconcile what had happened. The Lost Cause was a part of this and was directly opposed by the Emancipationist movement, which wanted to focus on the end of slavery and the rights of the formerly enslaved in the post-war order as the key outcomes and themes of the Civil War. In the middle was the Reconciliationist movement, which essentially cast aside the concerns of black Americans and favored reconciling the two (white) warring sides to return as fast as possible to business as usual.

The Reconciliationist stance eventually opened the door for the Lost Cause to take such a dominant place in the post-war narrative. It was easy for the victors to be sympathetic to their defeated opponents and allow them to push their propaganda when they knew they had won on the elements that really mattered to them.

The dominance of apolitical games within the American Civil War space essentially leaves the door open for Lost Cause inclined Neo-Confederates to enter the space and apply their own narratives to the games, narratives that the designers may never have intended. This would not be a problem if there was a robust barrier of games that engaged in the political that pushed back on this and made the stance of the wider hobby clear, but we can only rely on Mark Herman so much (prolific though he may be), and other designers need to factor the politics of the war (especially the role and impact of slavery!) into their designs.

These were not secondary factors to the war that can be left on the side. They were the very meat of the war itself and often had massive impacts on the shape and outcome of individual campaigns, and thus the battles that occurred on those campaigns. The politics of the 1860s cannot and should not be ignored.

Conclusion, for now

I feel like this should go without saying, but experience has taught me otherwise: I am not accusing any designers, artists, or publishers that I mentioned in this piece of being rebel flag waving Neo-Confederates obsessed with a return to the “Old South”. I am engaging in a work of cultural analysis and criticism. These games are both works of art and statements (whether explicitly or implicitly) about how we as a hobby view and remember history, and as such they are worthy of critical examination to see what the media we consume says about us.

I include myself in that–I was taught Lost Cause myths growing up, I believed them until I was taught actual history that helped me shake off the lies and see with clearer eyes. The Lost Cause is dangerous precisely because it has been so persuasive and omnipresent for so long.

Believing the Lost Cause’s lies is not a sin or moral failing. However, you must be prepared to face the truth even if it is uncomfortable to admit that you were once wrong (as I was).

This is also a project to study how games have changed over time and how we may have learned (or not) from past mistakes. It is also a work in progress. These are initial thoughts and very likely they will change in the next few years as I play even more games, read more books, and think even more on the topic. No opinion has to be set in stone for all time–not mine and not yours either.

Recommended Reading:

Ty Seidule, Robert E Lee and Me

David Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory

Kevin Levin, Searching for Black Confederates

Gary Gallagher and Alan Nolan (eds.), The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History

James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom

Elizabeth Varon, Armies of Deliverance

Games Played (so far)

- Manassas, designed by Rick Britton

- Shenandoah: Jackson’s Valley Campaign, designed by Tom Dalgliesh and Gary Selkirk

- The Late Unpleasantness, designed by Steve Ruwe

- Seven Pines; or, Fair Oaks, by Amabel Holland

- Into the Woods, designed by Richard Whitaker and Richard Berg

- Dead of Winter, designed by Richard Berg and David Powell

- Antietam 1862, Shiloh 1862, and The Seven Days Battles, designed by Mike and Grant Wylie

- Cedar Mountain 1862, designed by Pascal Toupy

- Shiloh: April Glory, designed by Tom and Grant Dalgliesh

- Stonewall Jackson’s Way II, designed by Joseph M. Balkoski, Ed Beach, Mike Belles, and Chris Withers

- Stonewall in the Valley, designed by Joseph M. Balkoski

- Longstreet Attacks, designed by Hermann Luttmann

- In Magnificent Style,designed by Hermann Luttmann

- The Day Was Ours, designed by Matt Ward

- Grand Havoc, designed by Jeff Grossman

- Battle Cry, designed by Richard Borg

- Jeff Davis, designed by R. Ben Madison

- Mosby’s Raiders, designed by Eric Lee Smith

- Rebel Fury, designed by Mark Herman

- Fire on the Mountain, designed by John Poniske

- Glory, by Richard Berg

Dr Stuart Ellis-Gorman has a passion for the Middle Ages and medieval archery born of a childhood fascination with Robin Hood and Lord of the Rings. He made a special study of the history of the longbow and the crossbow for his PhD at Trinity College Dublin and has presented on the medieval crossbow at multiple academic conferences. He is an active and award-winning contributor to the internet’s largest public history forum, /r/AskHistorians, and reviews history books for a range of academic publications. He lives in Ireland with his wife and daughter. He can be contacted through his website.

Thanks for a very thoughtful (and thought-provoking) piece, Stuart. When gamers bemoan the lack of in-depth writing in our hobby, disappointed by superficial descriptions instead of actual reviews, or complaining about unboxing videos…THIS is just the sort of article they should want instead. I’ve been eagerly following your & Pierre’s project through the podcast, hoping it both reaches your desired conclusion (for you) and never really ends (for me).

Of course I know that some of your expressed opinions have become a lightning rod within our hobby. That’s ok. Perhaps you anticipated it. You’re sticking to your guns and backing it up with data and references (e.g. your points about battle flags). One doesn’t have to agree with all of your viewpoints to learn a lot from the exploration and constructively engage in the discussion.

On the interesting topic of “Confederate Language,” what do you make of wargame titles A House Divided (without the subtitle) and For The People, both of which come from Union President and Commander in Chief Lincoln? True, he was referencing the Bible for the first one, but in the context of wargames about this conflict I’d maintain we’re thinking of Lincoln when we hear that title. (Then again, I imagine Lincoln was a proto-Reconciliationist, which you say opens the door too widely for the Lost Cause.)

Keep it up, and we’ll keep listening. Thanks again to you & Pierre.

-Mark

I agree with Mark entirely. I’ve been listening to Stuart and Pierre’s series since the beginning and promoting it on my own podcast and website. It gets me in trouble with listeners/readers who don’t take the time to actually engage with the material, but that’s how things go in the internet age.