This article is from Rob Doane, curator of the U.S. Naval War College Museum in Newport, Rhode Island. (Its Founders Hall location is seen at right above, next to Luce Hall at left.) The museum is the host for SDHistCon East, which will next be held August 8-11, 2024 (with very limited tickets going on sale April 6 at noon Pacific). You can read more about last year’s event there here, and more about of the history of the college here. Rob’s article on famed admiral Chester Nimitz’s time at the college, and the post-World War II speech he gave at the college about the value of this time there, follows.

On July 7, 1908, the Bainbridge-class destroyer USS Decatur ran aground while attempting to enter Batangas Harbor in the Philippines. Its commanding officer was a young ensign who had graduated from the Naval Academy just three years earlier and was still developing his seamanship skills. On this day, he made a poor decision to cross the sandbar that sat astride the entrance to the harbor even though he was unsure of his exact position and had failed to check the tide tables. One can only imagine the dread he must have felt when he heard the hull scraping bottom.

Luckily for him, a cargo ship helped free Decatur the next morning, and the destroyer suffered no serious damage. Nevertheless, his chain of command decided they had to hold the young officer accountable. He was court-martialed and accused of “culpable inefficiency in the performance of duty.” Everyone agreed that he had caused the mishap due to his own negligence, and the ensign did not deny his guilt. For a while it looked like his career was in jeopardy. But one of the admirals he had served under, perhaps recognizing something in him that hinted at his potential, testified on his behalf: “This is a good officer and will take more care in the future.” The court-martial panel members decided to issue a letter of reprimand and found him guilty of the lesser charge of hazarding his ship.

In today’s Navy, running your ship aground will end an officer’s career on the spot. Fortunately for Ensign Chester W. Nimitz, the Navy of the early twentieth century was more forgiving. His superiors, apparently concluding that he was not cut out for surface duty, reassigned him to submarines. Nimitz made the most of his second chance and used the opportunity to learn about the emerging field of submarine warfare. The Navy saw fit to promote him five more times over the next 30 years, and as a result, the right man for the job was available when the U.S. and Japan went to war in 1941.

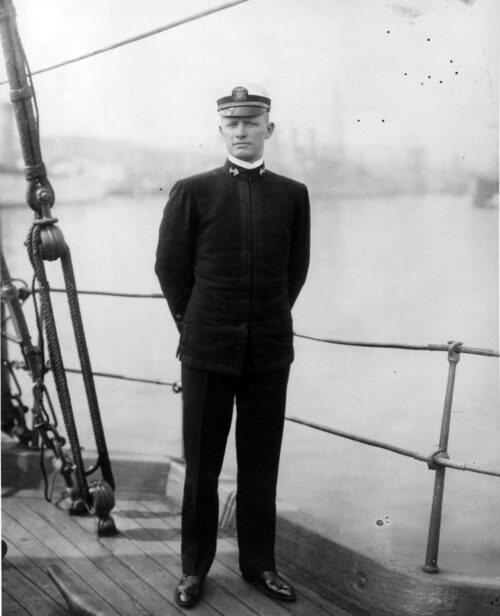

Ensign Chester Nimitz in 1907. (U.S. Navy photo, Photo #: NH 49740. Via dvidshub.net.)

Before he could lead the war in the Pacific, Nimitz had to learn the art and science of naval warfare. The place to do that in the 1920s was the Naval War College (NWC) in Newport, RI. The school had been founded in 1884 due to the efforts of Admiral Stephen B. Luce who realized that the Naval Academy, while a fine school, couldn’t teach officers everything they needed to know over the course of their careers. At some point, he argued, an officer needed to take a break from sea duty and return to school to study the problems that only concerned captains and admirals. These topics included strategy, logistics, and international law.

The first few decades of the College’s existence were tenuous, with many inside the Navy and some in government questioning the need for such a school. But as NWC graduates filtered into high level staff positions and began shaping Navy policy, the value of their education became apparent. By the time Nimitz arrived in 1922, the Navy considered the College a key part of its system for formulating strategy and preparing officers to exercise command at the highest levels.

The training that NWC students received was designed to instill a spirit of aggressiveness and an offensive mindset. This had been baked into the College’s DNA by one of its first faculty members, Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, who compiled his lectures into the seminal work, The Influence of Seapower Upon History.

A tenet of Mahan’s philosophy was that navies should be organized with the object of fighting a single decisive battle against an enemy fleet to establish control of the seas. In the early twentieth century, the U.S. Navy still did not have a major fleet battle in its own history to offer as a teaching example, so NWC staff used European naval battles such as Trafalgar for their classroom discussions.

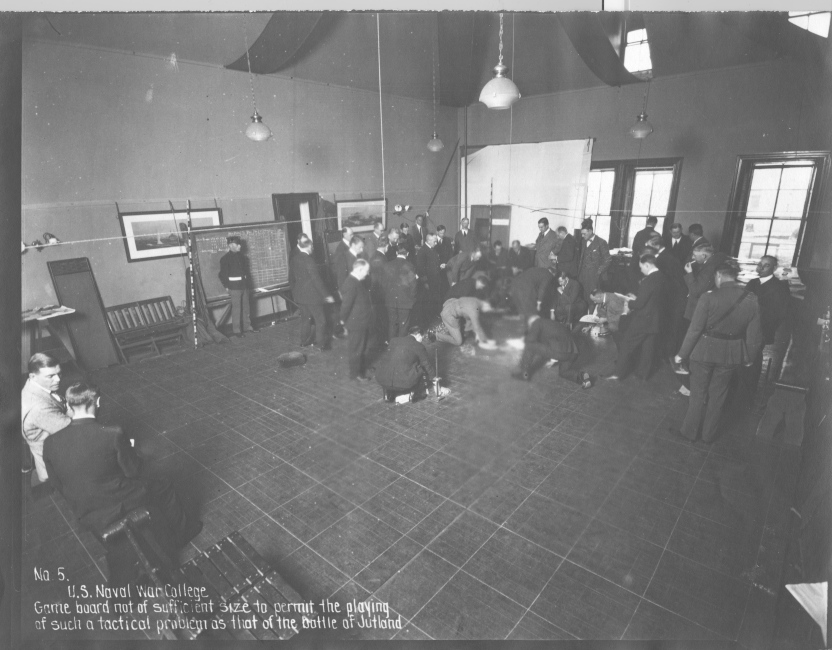

When Nimitz began his studies, Jutland was just six years in the past and offered plenty of fodder for budding strategists to debate. Every student at the College was required to study the battle in detail and write a paper analyzing the decisions made by the principal commanders. Nimitz would have taken part in wargames in Luce Hall (exterior seen at left at top next to Founders Hall, which houses the museum; interior seen below).

Wargaming in Luce Hall at the U.S. Naval War College in the 1920s. Nimitz took part in wargames here while attending the college.

One of the primary lessons the U.S. Navy took away from this battle was that Admiral John Jellicoe of the Grand Fleet was not aggressive enough and allowed the German High Seas Fleet to escape during the night of May 31-June1. In the decades that followed, students at the NWC, including Nimitz, found fault with Jellicoe’s actions, especially criticizing his use of destroyers and his decision to turn away from the High Seas Fleet to avoid torpedo attacks.1

As the Pacific Ocean took on greater importance after World War I, the wargaming faculty added a game to the curriculum. This scenario pitted the U.S. against Japan in a strategic-level game that became the basis for Plan Orange, one of many contingency plans hashed out by the Navy and War Departments in the 1920s and 30s. Plan Orange underwent many revisions, but each version was based on the premise of taking action to cross the Pacific and force a conclusion to the war in Japanese waters. NWC students always assumed their side would be the ones carrying the war to the enemy.

When the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor placed the Navy on defense during the opening stages of the war in the Pacific, it came as a shock to many officers who were not conditioned to think in those terms. True to their training, senior officers like Nimitz and Ernest J. King looked for opportunities to reclaim the initiative, if only temporarily. This mindset, instilled largely through wargaming at the NWC, ultimately produced the carrier raids executed by USS Enterprise, USS Yorktown, USS Lexington, and USS Hornet in February and March of 1942. The true value of wargaming was not to rehearse specific plans or to memorize a set of pre-programmed responses to enemy actions, but to train future commanding officers to analyze information, adapt to unforeseen circumstances, and act decisively even with imperfect intelligence.

The College’s focus on Jutland during the interwar period has led some critics to accuse it of fostering a “gun club” mentality at a time when new technology was making battleships less relevant. Through the 1980s, historians commonly found fault with the College’s curriculum, claiming that it produced officers obsessed with fighting climactic battles between lines of battleships while ignoring developments in other arms of the fleet. Because students spent so much time refighting Jutland, the argument went, they never learned how to use aircraft carriers and submarines and were forced to catch up to their German and Japanese counterparts when war broke out.2

Far from being stuck in the past, NWC students spent considerable time reflecting on new technology and the changing nature of naval warfare. Many of them devoted entire chapters of their student papers to analyzing the different elements of the fleet and offering guidance about each one’s employment in future battles. Submarines, destroyers, and aircraft were the most frequently discussed platforms. Indeed, naval aviation received an enormous amount of attention in Newport during the interwar period. Understanding the importance of controlling the air just as they had been taught to control the sea, students anticipated the struggle for air superiority that featured so prominently in operational planning during World War II.

In his thesis on tactics, Nimitz made several prescient observations about war at sea in the early twentieth century. Many of the games run at the College during this timeframe assumed the war would begin with a surprise attack, and Nimitz was no exception. He thought Japan would be “fully prepared at the outbreak of trouble and that BLUE [the U.S.] will be but indifferently prepared.” Furthermore, he predicted that the war would begin “at a time best suited to ORANGE as the result of carefully planned acts of aggression calculated to provoke a declaration of war on the part of BLUE.”3 While most games in Newport ran under the assumption that the surprise attacks would be limited to the Philippines and Guam, the basic idea was not far off the mark.

Aircraft carriers were still in their infancy at the time Nimitz was writing. The major navies of the world viewed them as secondary units primarily suited to scouting and observation, but even at this stage, their potential as true attack platforms was apparent. In their BLUE vs. RED games that simulated a hypothetical war with Great Britain, Nimitz and his contemporaries thought aircraft were essential in forcing the battle to develop along lines that were favorable to the U.S. fleet.

In Nimitz’s view, naval aircraft were best used for three missions. First, they should observe enemy formations while screening the U.S. fleet from enemy scouts. Second, they should attack enemy aircraft carriers in order to prevent aircraft from taking off. Finally, they should employ bomb and torpedo attacks to force the RED fleet to turn toward BLUE and close the range (this would nullify RED’s one-knot overall speed advantage as well as its greater firepower at ranges beyond 15,000 yards).4

Given Nimitz’s earlier experience on submarines, it should come as no surprise that he wrote extensively about their employment in battle too. Germany’s World War I U-boat campaign against merchant shipping had provoked such outrage in the U.S. that naval officers could not foresee the U.S. Navy using submarines that way. Like aircraft carriers, submarines were considered auxiliary units whose job was to support the main battle fleet.

While Nimitz did not envision submarines conducting sustained independent operations, he did foresee the devastating impact that submarines could have on surface ships as they tried to bring the enemy to battle. He considered a submarine’s most important targets to be aircraft carriers, battleships, battle cruisers, and light cruisers in that order.5

Early versions of Plan Orange envisioned a “through-ticket” strategy in which the American fleet would sail across the Pacific to fight a decisive battle with the Japanese near Guam or the Philippines. It sounded good on paper, but when NWC students tried to implement this plan on the wargaming floor, their fleets suffered so much attrition from submarines, air attacks, and mechanical breakdowns, that they were no longer in any condition to fight upon arrival in the theater of battle.

Gradually, students and faculty helped develop an alternative strategy that utilized a step-by-step approach to confronting the Japanese fleet. Rather than attempting a single lunge across the Pacific Ocean and hoping for the best, the Navy would advance from island to island in incremental steps, always pausing to build bases and bring forward supplies before taking the next step.6

Nimitz was among those who recognized that a single decisive battle in the tradition of Mahan wasn’t a realistic expectation given the vast distances and enemy forces involved in the Pacific: “To bring such a war to a successful conclusion BLUE must either destroy ORANGE military and naval forces or effect a complete isolation of ORANGE country by cutting all communication with the outside world….In either case the operations imposed upon BLUE will require a series of bases westward from Oahu, and will require the BLUE fleet to advance westward with an enormous train, in order to be prepared to seize and establish bases enroute.”7

One of the great benefits of wargaming at the NWC was that students became intimately familiar with the geography of the Pacific Ocean. Identifying which islands had suitable harbors, which atolls could hold air strips, and how far a surface force could advance before refueling were all key to winning these games. The discussions generated by these games helped inform the work of the Joint Army-Navy Board as it developed the plans ultimately used to guide operations during World War II.

24 days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Rear Admiral Chester Nimitz received a promotion to full admiral and took over command of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. By April 1942, he assumed the additional duties of Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas, and prepared to direct the Navy’s drive across the Central Pacific toward the Japanese home islands.

Both jobs carried an enormous amount of responsibility. Combined, there were probably only a handful of officers capable of shouldering the load. Nimitz surely needed every bit of preparation he had received up to this point. Indeed, his year of study at the Naval War College had taught him how to think in strategic terms and organize complex operations.

Years later, in an address to the graduating class at the Naval War College, Nimitz reflected on the value of wargaming in shaping the grand strategy of the war in the Pacific. He recounted the many hours he had spent on the wargaming floor in Luce Hall as a student and concluded that “the war with Japan had been reenacted in the game rooms here by so many people and in so many different ways that nothing that happened during the war was a surprise – absolutely nothing except the kamikaze tactics towards the end of the war; we had not visualized those.”8

This oft-repeated quote should not be taken too literally, as there were clearly other events in the war – Pearl Harbor being the most obvious – that took the U.S. by surprise. Nimitz’s observation also revealed some of the self-imposed limitations under which the NWC operated in the 1920s that limited the effectiveness of wargames. In this critical period of the College’s history, there was no one on the staff knowledgeable enough about the Japanese military to recognize that kamikaze attacks might be contemplated by their high command.

The officer ranks of the U.S. Navy during the interwar period were composed almost entirely of Americans of European descent. Japanese Americans, while not prohibited by policy from joining the Navy, faced numerous obstacles to becoming officers, let along being promoted to the upper ranks. Someone born in Japan who was familiar with their military culture stood no real chance of becoming a student at the NWC where they might contribute to discussions about strategy and policy. If the Navy had recruited from a wider cross section of the U.S. population, perhaps this critical mistake could have been avoided.

What Nimitz was really trying to convey to his audience was the sense of confidence he felt when he took over as CINCPAC-CINCPOA, born out of an intimate familiarity with the Pacific Theater. He knew what needed to happen to defeat Japan because he had already thought through the major problems as a student wargamer. By 1942, the island-hopping campaign had been played out hundreds of times in Newport. The sequence of invasions and battles never unfolded exactly as they did in the real war, but they often came close.

The purpose of the games was not to produce a “perfect plan” that would simply be dusted off in wartime and followed like a recipe from a cookbook. Rather, the point was to provide a learning laboratory where senior officers could think about what elements contributed to victory in war. By playing out the war with Japan, future admirals like Nimitz got a sneak preview of the theater whose geography they understood on a deep level by the time they graduated. By exercising high command in a wargaming environment where they were allowed to fail and learn from their mistakes, Nimitz and his classmates were better prepared to direct the war against Japan when actual human lives were at stake.

Rob Doane is a public historian and museum professional who has worked in maritime museums since 2005. He earned a BA in history from the University of Michigan and a MA in public history from Loyola University Chicago. After beginning his career as a historical interpreter at the USS Constitution Museum, Mr. Doane joined the curatorial staff of the Norman Rockwell Museum in 2008. From 2010-2012, he served as the Curator of the Beverley R. Robinson Print Collection at the U.S. Naval Academy Museum where he oversaw the preservation and interpretation of approximately 5,000 historic prints depicting European and American naval history. He has presented papers to the Society for Military History, the McMullen Naval History Symposium, and the Maritime Heritage Conference. He is currently the Curator of the Naval War College Museum in Newport, RI, where he oversees the museum’s collecting and exhibition programs. You can find out more about the museum on their website, their Facebook page, and their Twitter and Instagram pages.

1. See for example Captain Clarence A. Abele, “Tactics,” 15 February 1921, 25-27, RG 13, box 3, NWC Archives; Lieutenant James L. Holloway, Jr., “Destroyer Operations at the Battle of Jutland,” 30 October 1930, 19, RG 13, box 9, NWC Archives; Richard L. Conolly, “Destroyer Operations at the Battle of Jutland,” 30 October 1930, 25-26, RG 13, box 9, NWC Archives. ↩

2. Examples of these arguments can be found in Clark G. Reynolds, The Fast Carriers: The Forging of an Air Navy (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1968), 165; Ronald H. Spector, Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan (New York: The Free Press, 1985), 19; Russell F. Weigley, The American Way of War: A History of American Military Strategy and Policy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1977), 293-295. ↩

3. Commander Chester W. Nimitz, “Tactics,” 28 April 1923, 34, RG 13, box 5, NWC Archives.↩

4. Ibid., 15. ↩

5. Ibid., 15. ↩

6. For a detailed account of the history behind Plan Orange and its development, see Edward S. Miller, War Plan Orange: The US Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897-1945 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2013). ↩

7 Nimitz, “Tactics,” 35.↩

8 Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz (Ret.), Address to the Naval War College, October 10, 1960, RG 15, box 31, NWC Archives.↩